CONTENTS

1 BROADCAST VIDEO RECORDING

2 DOMESTIC VIDEO RECORDING (ANALOGUE)

3 DOMESTIC VIDEO RECORDING (DIGITAL)

I never worked in television, and have no hands-on experience of professional video recording: so this isn't a detailed technical history, just an examination of the effect the capability had on television (and followed by an examination of the effect domestic video recording had on viewers - an area I do have experience in).

The

early low-quality Baird

30-line system never really

got beyond the

experimental stage, though there were transmissions for a time before

the higher quality 405-line EMI system took over. The Baird system was

such low-bandwidth that its signal could be recorded on a 78rpm record,

and a few experiments were done with this. A friend of mine had one of

these 78s, and wasted a considerable amount of time trying to get it to

play, without sucess.

The

early low-quality Baird

30-line system never really

got beyond the

experimental stage, though there were transmissions for a time before

the higher quality 405-line EMI system took over. The Baird system was

such low-bandwidth that its signal could be recorded on a 78rpm record,

and a few experiments were done with this. A friend of mine had one of

these 78s, and wasted a considerable amount of time trying to get it to

play, without sucess.

When the

television service reopened after the

war, using the same

405-line format, all programmes were live. If a programme was repeated,

it had to be re-performed. 'Telerecording'

- filming from a

television screen onto 35mm or 16mm film (known as 'Kinetoscopes' in

the USA) was introduced in 1947, but the quality was extremely

poor. Improvements were made in time for the 1953 Coronation

procession and

service to be telerecorded (though of course it was all broadcast

live), but even so the degradation in quality was immediately

noticeable even to the untrained eye. A few programmes were recorded in

advance, or given repeats using telerecording, but the reduced quality

made the programme much less effective for viewers: and the process was

also expensive and of course required the film to go through the usual

development and printing process.

When the

television service reopened after the

war, using the same

405-line format, all programmes were live. If a programme was repeated,

it had to be re-performed. 'Telerecording'

- filming from a

television screen onto 35mm or 16mm film (known as 'Kinetoscopes' in

the USA) was introduced in 1947, but the quality was extremely

poor. Improvements were made in time for the 1953 Coronation

procession and

service to be telerecorded (though of course it was all broadcast

live), but even so the degradation in quality was immediately

noticeable even to the untrained eye. A few programmes were recorded in

advance, or given repeats using telerecording, but the reduced quality

made the programme much less effective for viewers: and the process was

also expensive and of course required the film to go through the usual

development and printing process.

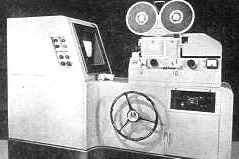

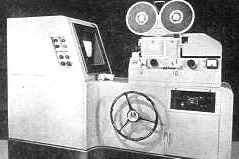

By 1958, though the quality of at least 35mm telerecordings was reasonably good (though four times more expensive in film stock than 16mm), the great success of audio tape recording in radio prompted the search for an equivalent in television: something easy to handle, flexible, editable, and to all intents and purposes indistinguishable from a live broadcast. The BBC Research Department set to work, and by April 1958 was able to demonstrate 'VERA' (Vision Electronic Recording Apparatus).

The machine was

unwieldy, and used huge reels of

½-inch tape travelling at an insane 200

inches per

second (the speed necessary to handle the very high bandwidth of a

video signal, and over 11 miles per hour!). It was given a live

demonstration on-air in Panorama

on April

14th 1958; I well remember seeing this. Richard Dimbleby, seated by a

clock, talked for a couple of minutes about the new method of vision

recording with an instant playback, and then the tape was wound back

and replayed. The picture was slightly watery, but reasonably

watchable, and of course instant playback was something completely new.

(You can see this part of the transmission here.)

The machine was

unwieldy, and used huge reels of

½-inch tape travelling at an insane 200

inches per

second (the speed necessary to handle the very high bandwidth of a

video signal, and over 11 miles per hour!). It was given a live

demonstration on-air in Panorama

on April

14th 1958; I well remember seeing this. Richard Dimbleby, seated by a

clock, talked for a couple of minutes about the new method of vision

recording with an instant playback, and then the tape was wound back

and replayed. The picture was slightly watery, but reasonably

watchable, and of course instant playback was something completely new.

(You can see this part of the transmission here.)

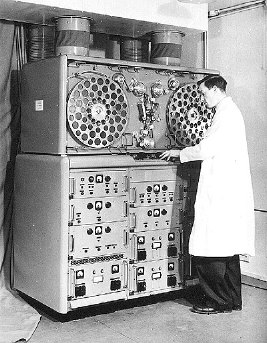

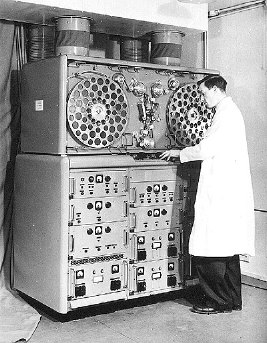

However, VERA was an evolutionary dead end and as far as I know that was the only time it was ever used on-air. At about the same time, the American Ampex Corporation demonstrated its solution to the problem: this used 2-inch wide tape travelling at a more manageable 15 inches per second, achieving the high contact speed needed for video by means of rapidly rotating heads which scanned the tape from top to bottom in a series of very slightly diagonal adjacent tracks (with normal linear tracks along the tape edge carrying sound and synchronization pulses). The quality was indistinguishable from a live transmission.

VERA was quietly

retired, though it has been

suggested that Ampex were

initially reluctant to let the BBC have their machines, and VERA

provided a lever in persuading them.

VERA was quietly

retired, though it has been

suggested that Ampex were

initially reluctant to let the BBC have their machines, and VERA

provided a lever in persuading them.

The first machine was installed at Lime Grove in October 1958, followed by a second in January and two more shortly afterwards. They were seen as being most use to Sport, who would probably have liked to monopolize them; but the star power of Tony Hancock - whose Hancock's Half Hour was extremely popular but who notoriously had difficulty learning his lines - enabled Variety Department to get access to the machine for this show.

Up until then all the transmissions had been live, and Hancock had had the alarming experience of a show going badly wrong on-air; so the desire was to be able to record the show in short sections and assemble it, so that retakes would be easier.

Though audio tape could easily be cut-and-spliced, the problem with video tape was that the synchronization pulses had to be exactly maintained or the picture would roll. The engineers were of the opinion that the whole idea was impossible; but Hancock's producer, Duncan Wood, got hold of a spare recording of a variety show called On The Bright Side and physically edited the programme down from 45 to 25 minutes: with the concept proved, the process of pre-recording and editing Hancock's shows could go ahead.

Though in theory it was possible to edit within scenes this was generally avoided because even with care there could be a slight hiccup in the picture at the edit - I remember noticing this on many occasions - so the tendency was to edit only on fades to black between scenes.

Once the technique became widespread the impact on production was considerable. In drama for example: if you look at the published scripts for Nigel Kneale's famous Quatermass series (1953), it's rather obvious that, since they were performed live, each scene begins with a minute or so of minor characters filling time to allow the principal actors to get from the previous set to the current one. With editing this became no longer necessary. Gradually many more shows were assemble-edited in this way, until by the present day only a small minority of programmes are live.

Further developments in studio-based video recording were concerned with improving the quality (and lowering the cost), and coping with 625 lines and colour. Helical-scan

machines became the norm, using a

slightly angled rotating head drum which the tape wrapped round: this

was cheaper and more reliable than the original Ampex

system. Perhaps more importantly, the actual physical cutting of the

very expensive tape was abandoned in favour of 'dub-editing', where the

successive sections of a recording were assembled by copying onto a new

tape, with the equipment designed to achieve this in a way which

wouldn't cause visible glitches. (As this didn't damage the tape, it

could be easily re-used, so many programmes were wiped after

transmission - a policy since regretted with the advent of the sales

opportunities provided by home video).

In more recent years the analogue

methods were replaced by digital recording, but of

course none of this

was noticeable to the viewer.

Helical-scan

machines became the norm, using a

slightly angled rotating head drum which the tape wrapped round: this

was cheaper and more reliable than the original Ampex

system. Perhaps more importantly, the actual physical cutting of the

very expensive tape was abandoned in favour of 'dub-editing', where the

successive sections of a recording were assembled by copying onto a new

tape, with the equipment designed to achieve this in a way which

wouldn't cause visible glitches. (As this didn't damage the tape, it

could be easily re-used, so many programmes were wiped after

transmission - a policy since regretted with the advent of the sales

opportunities provided by home video).

In more recent years the analogue

methods were replaced by digital recording, but of

course none of this

was noticeable to the viewer.

What was noticeable was the introduction of mobile video. For many years sections of plays which were set out of doors had to be pre-filmed, usually on 16mm, and the quality difference was always noticeable and detracted from the smooth flow of the play. Mobile video recording was possible, but required a vanload of equipment and a mains generator (film only required a camera and a portable audio recorder, both running on batteries).

The introduction of

combined cameras and video

recorders (the term 'camcorder' only came in later) made a huge

difference to outdoor inserts. Sony's BetaCam,

introduced in 1982, used

the same physical size of cassette as the domestic Betamax machines,

but using a different recording technique and running at around six

times the speed.

The introduction of

combined cameras and video

recorders (the term 'camcorder' only came in later) made a huge

difference to outdoor inserts. Sony's BetaCam,

introduced in 1982, used

the same physical size of cassette as the domestic Betamax machines,

but using a different recording technique and running at around six

times the speed.

Now a single operator could take a portable camera into a news situation, or a small team could easily record feature or drama inserts. The camera became the industry standard for many years, and improvements in quality meant that, as with studio-based recording, viewers could see no difference in the quality. The lack of the distraction caused by a visible change of formats made the programmes seem more immediate, and the flexibility made it quicker, cheaper and easier to produce programmes. The development, some years later, of portable digital systems together with relatively inexpensive digital editing, meant that a whole programme could be shot and edited by a team of only three or four people - thus leading to the perhaps undesirable rise of 'reality TV' about people's houses or other subjects not requiring expensive preparation.

However one thing did not change for the viewer until around 1980: if you wanted to see a programme you had to watch it as it was transmitted. If you missed it (and it wasn't repeated) you had missed it, and that was that. The change to viewing habits caused by the availability of domestic video recording will be examined on the next page.

1 BROADCAST VIDEO RECORDING

2 DOMESTIC VIDEO RECORDING (ANALOGUE)

3 DOMESTIC VIDEO RECORDING (DIGITAL)

I never worked in television, and have no hands-on experience of professional video recording: so this isn't a detailed technical history, just an examination of the effect the capability had on television (and followed by an examination of the effect domestic video recording had on viewers - an area I do have experience in).

The

early low-quality Baird

30-line system never really

got beyond the

experimental stage, though there were transmissions for a time before

the higher quality 405-line EMI system took over. The Baird system was

such low-bandwidth that its signal could be recorded on a 78rpm record,

and a few experiments were done with this. A friend of mine had one of

these 78s, and wasted a considerable amount of time trying to get it to

play, without sucess.

The

early low-quality Baird

30-line system never really

got beyond the

experimental stage, though there were transmissions for a time before

the higher quality 405-line EMI system took over. The Baird system was

such low-bandwidth that its signal could be recorded on a 78rpm record,

and a few experiments were done with this. A friend of mine had one of

these 78s, and wasted a considerable amount of time trying to get it to

play, without sucess. When the

television service reopened after the

war, using the same

405-line format, all programmes were live. If a programme was repeated,

it had to be re-performed. 'Telerecording'

- filming from a

television screen onto 35mm or 16mm film (known as 'Kinetoscopes' in

the USA) was introduced in 1947, but the quality was extremely

poor. Improvements were made in time for the 1953 Coronation

procession and

service to be telerecorded (though of course it was all broadcast

live), but even so the degradation in quality was immediately

noticeable even to the untrained eye. A few programmes were recorded in

advance, or given repeats using telerecording, but the reduced quality

made the programme much less effective for viewers: and the process was

also expensive and of course required the film to go through the usual

development and printing process.

When the

television service reopened after the

war, using the same

405-line format, all programmes were live. If a programme was repeated,

it had to be re-performed. 'Telerecording'

- filming from a

television screen onto 35mm or 16mm film (known as 'Kinetoscopes' in

the USA) was introduced in 1947, but the quality was extremely

poor. Improvements were made in time for the 1953 Coronation

procession and

service to be telerecorded (though of course it was all broadcast

live), but even so the degradation in quality was immediately

noticeable even to the untrained eye. A few programmes were recorded in

advance, or given repeats using telerecording, but the reduced quality

made the programme much less effective for viewers: and the process was

also expensive and of course required the film to go through the usual

development and printing process.By 1958, though the quality of at least 35mm telerecordings was reasonably good (though four times more expensive in film stock than 16mm), the great success of audio tape recording in radio prompted the search for an equivalent in television: something easy to handle, flexible, editable, and to all intents and purposes indistinguishable from a live broadcast. The BBC Research Department set to work, and by April 1958 was able to demonstrate 'VERA' (Vision Electronic Recording Apparatus).

The machine was

unwieldy, and used huge reels of

½-inch tape travelling at an insane 200

inches per

second (the speed necessary to handle the very high bandwidth of a

video signal, and over 11 miles per hour!). It was given a live

demonstration on-air in Panorama

on April

14th 1958; I well remember seeing this. Richard Dimbleby, seated by a

clock, talked for a couple of minutes about the new method of vision

recording with an instant playback, and then the tape was wound back

and replayed. The picture was slightly watery, but reasonably

watchable, and of course instant playback was something completely new.

(You can see this part of the transmission here.)

The machine was

unwieldy, and used huge reels of

½-inch tape travelling at an insane 200

inches per

second (the speed necessary to handle the very high bandwidth of a

video signal, and over 11 miles per hour!). It was given a live

demonstration on-air in Panorama

on April

14th 1958; I well remember seeing this. Richard Dimbleby, seated by a

clock, talked for a couple of minutes about the new method of vision

recording with an instant playback, and then the tape was wound back

and replayed. The picture was slightly watery, but reasonably

watchable, and of course instant playback was something completely new.

(You can see this part of the transmission here.)However, VERA was an evolutionary dead end and as far as I know that was the only time it was ever used on-air. At about the same time, the American Ampex Corporation demonstrated its solution to the problem: this used 2-inch wide tape travelling at a more manageable 15 inches per second, achieving the high contact speed needed for video by means of rapidly rotating heads which scanned the tape from top to bottom in a series of very slightly diagonal adjacent tracks (with normal linear tracks along the tape edge carrying sound and synchronization pulses). The quality was indistinguishable from a live transmission.

VERA was quietly

retired, though it has been

suggested that Ampex were

initially reluctant to let the BBC have their machines, and VERA

provided a lever in persuading them.

VERA was quietly

retired, though it has been

suggested that Ampex were

initially reluctant to let the BBC have their machines, and VERA

provided a lever in persuading them.The first machine was installed at Lime Grove in October 1958, followed by a second in January and two more shortly afterwards. They were seen as being most use to Sport, who would probably have liked to monopolize them; but the star power of Tony Hancock - whose Hancock's Half Hour was extremely popular but who notoriously had difficulty learning his lines - enabled Variety Department to get access to the machine for this show.

Up until then all the transmissions had been live, and Hancock had had the alarming experience of a show going badly wrong on-air; so the desire was to be able to record the show in short sections and assemble it, so that retakes would be easier.

Though audio tape could easily be cut-and-spliced, the problem with video tape was that the synchronization pulses had to be exactly maintained or the picture would roll. The engineers were of the opinion that the whole idea was impossible; but Hancock's producer, Duncan Wood, got hold of a spare recording of a variety show called On The Bright Side and physically edited the programme down from 45 to 25 minutes: with the concept proved, the process of pre-recording and editing Hancock's shows could go ahead.

Though in theory it was possible to edit within scenes this was generally avoided because even with care there could be a slight hiccup in the picture at the edit - I remember noticing this on many occasions - so the tendency was to edit only on fades to black between scenes.

Once the technique became widespread the impact on production was considerable. In drama for example: if you look at the published scripts for Nigel Kneale's famous Quatermass series (1953), it's rather obvious that, since they were performed live, each scene begins with a minute or so of minor characters filling time to allow the principal actors to get from the previous set to the current one. With editing this became no longer necessary. Gradually many more shows were assemble-edited in this way, until by the present day only a small minority of programmes are live.

Further developments in studio-based video recording were concerned with improving the quality (and lowering the cost), and coping with 625 lines and colour.

Helical-scan

machines became the norm, using a

slightly angled rotating head drum which the tape wrapped round: this

was cheaper and more reliable than the original Ampex

system. Perhaps more importantly, the actual physical cutting of the

very expensive tape was abandoned in favour of 'dub-editing', where the

successive sections of a recording were assembled by copying onto a new

tape, with the equipment designed to achieve this in a way which

wouldn't cause visible glitches. (As this didn't damage the tape, it

could be easily re-used, so many programmes were wiped after

transmission - a policy since regretted with the advent of the sales

opportunities provided by home video).

In more recent years the analogue

methods were replaced by digital recording, but of

course none of this

was noticeable to the viewer.

Helical-scan

machines became the norm, using a

slightly angled rotating head drum which the tape wrapped round: this

was cheaper and more reliable than the original Ampex

system. Perhaps more importantly, the actual physical cutting of the

very expensive tape was abandoned in favour of 'dub-editing', where the

successive sections of a recording were assembled by copying onto a new

tape, with the equipment designed to achieve this in a way which

wouldn't cause visible glitches. (As this didn't damage the tape, it

could be easily re-used, so many programmes were wiped after

transmission - a policy since regretted with the advent of the sales

opportunities provided by home video).

In more recent years the analogue

methods were replaced by digital recording, but of

course none of this

was noticeable to the viewer.What was noticeable was the introduction of mobile video. For many years sections of plays which were set out of doors had to be pre-filmed, usually on 16mm, and the quality difference was always noticeable and detracted from the smooth flow of the play. Mobile video recording was possible, but required a vanload of equipment and a mains generator (film only required a camera and a portable audio recorder, both running on batteries).

The introduction of

combined cameras and video

recorders (the term 'camcorder' only came in later) made a huge

difference to outdoor inserts. Sony's BetaCam,

introduced in 1982, used

the same physical size of cassette as the domestic Betamax machines,

but using a different recording technique and running at around six

times the speed.

The introduction of

combined cameras and video

recorders (the term 'camcorder' only came in later) made a huge

difference to outdoor inserts. Sony's BetaCam,

introduced in 1982, used

the same physical size of cassette as the domestic Betamax machines,

but using a different recording technique and running at around six

times the speed. Now a single operator could take a portable camera into a news situation, or a small team could easily record feature or drama inserts. The camera became the industry standard for many years, and improvements in quality meant that, as with studio-based recording, viewers could see no difference in the quality. The lack of the distraction caused by a visible change of formats made the programmes seem more immediate, and the flexibility made it quicker, cheaper and easier to produce programmes. The development, some years later, of portable digital systems together with relatively inexpensive digital editing, meant that a whole programme could be shot and edited by a team of only three or four people - thus leading to the perhaps undesirable rise of 'reality TV' about people's houses or other subjects not requiring expensive preparation.

However one thing did not change for the viewer until around 1980: if you wanted to see a programme you had to watch it as it was transmitted. If you missed it (and it wasn't repeated) you had missed it, and that was that. The change to viewing habits caused by the availability of domestic video recording will be examined on the next page.