CONTENTS

1 BROADCAST VIDEO RECORDING

2 DOMESTIC VIDEO RECORDING (ANALOGUE)

3 DOMESTIC VIDEO RECORDING (DIGITAL)

Until the 1970s, television viewing was live: if you wanted to see a programme you had to arrange to be by a television when it was transmitted. Domestic video recording was a long wished-for facility, but though professional video recording had been around since 1958 it was phenomenally expensive and bulky (the Ampex machines cost a quarter of a million pounds each at 1960 prices).

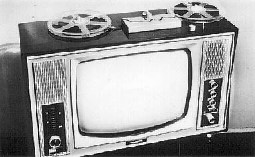

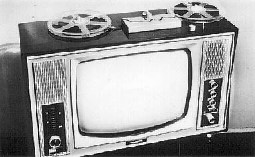

The

earliest attempt to

create a domestic video

recorder was as far

back as 1963: Telcan (right) was a television

with an open-reel

recorder

mounted on top, using linear recording running ¼ inch tape at

120

inches/second for a maximum

running time of 15 minutes.

The

earliest attempt to

create a domestic video

recorder was as far

back as 1963: Telcan (right) was a television

with an open-reel

recorder

mounted on top, using linear recording running ¼ inch tape at

120

inches/second for a maximum

running time of 15 minutes.  There

was no timer, so you had to be there

anyway to record something: the quality was poor, and it was

unreliable, so it's not surprising that it didn't make any

headway. By

the late 1960s various open-reel video recorders using ½ inch

tape and

rotating heads were available, of which one of the most common

makes

was Shibaden

(left): again, there was no timer, and the cost and difficulty

of

lacing it up meant that it wasn't suitable for the domestic

market

(though it was useful for semi-professionals); the quality was

fairly

good but the tape was expensive. (A friend of mine had a couple

and

used cheaply-bought second-hand computer tape - the quality was

just

about watchable but not pretty).

There

was no timer, so you had to be there

anyway to record something: the quality was poor, and it was

unreliable, so it's not surprising that it didn't make any

headway. By

the late 1960s various open-reel video recorders using ½ inch

tape and

rotating heads were available, of which one of the most common

makes

was Shibaden

(left): again, there was no timer, and the cost and difficulty

of

lacing it up meant that it wasn't suitable for the domestic

market

(though it was useful for semi-professionals); the quality was

fairly

good but the tape was expensive. (A friend of mine had a couple

and

used cheaply-bought second-hand computer tape - the quality was

just

about watchable but not pretty).

The

first successful domestic video recorder was the Philips

N1500 (right),

available from 1970 (1972 in the UK). It used tape in a

cassette, so

lacing up wasn't a problem; in order to acommodate the slanted

path

round the head drum the reels were placed one above the other in

the

cassette, which was roughly cubical in shape. The machine had a

primive

mechanical timer, so it would make unattended recordings, and

the

quality was quite acceptable. However the mechanical lace-up

round the

complicated tape path was liable to damage the tape; and the

machine

was quite expensive at £400 (and so was the tape); it was never

widely

bought, though well-off enthusiasts bought enough to make later

improved versions worth manufacturing.

The

first successful domestic video recorder was the Philips

N1500 (right),

available from 1970 (1972 in the UK). It used tape in a

cassette, so

lacing up wasn't a problem; in order to acommodate the slanted

path

round the head drum the reels were placed one above the other in

the

cassette, which was roughly cubical in shape. The machine had a

primive

mechanical timer, so it would make unattended recordings, and

the

quality was quite acceptable. However the mechanical lace-up

round the

complicated tape path was liable to damage the tape; and the

machine

was quite expensive at £400 (and so was the tape); it was never

widely

bought, though well-off enthusiasts bought enough to make later

improved versions worth manufacturing.

In 1971 Sony introduced the U-matic video cassette recorder: it was aimed at the professional market and far too expensive for domestic use, but it paved the way for future developments: the tape was enclosed in a fairly bulky cassette, but with the spools on the same level, the slanted wrap round the head drum being achieved by placing the drum at a slight angle. This made the lacing process much easier and more reliable. The

machine became an industry standard for some years for making

copies

for viewing or testing television recordings, but was far too

expensive

for domestic use. However in 1975 Sony released a scaled-down

and

simplified machine called 'Betamax'. The

cassettes

(left) used

½

inch tape, were a more manageable size, and ran for 3¼ hours;

there was

a digital timer which could also select the TV channel, so that

successive recordings from different channels became possible.

The

machine became an industry standard for some years for making

copies

for viewing or testing television recordings, but was far too

expensive

for domestic use. However in 1975 Sony released a scaled-down

and

simplified machine called 'Betamax'. The

cassettes

(left) used

½

inch tape, were a more manageable size, and ran for 3¼ hours;

there was

a digital timer which could also select the TV channel, so that

successive recordings from different channels became possible.

JVC introduced a rival version called VHS ('Video Home System') which worked on basically the same principles, though with differences in the mechanics of the lace-up and the way the tracks were placed on the tape (in particular the machine unlaced every time it was stopped, whereas Betamax kept the tape laced until it was ejected). The cassettes ran for 3 hours (longer in the USA because of the different picture standards). The quality was inferior to Betamax, but while in the USA Betamax was the preferred domestic system for some years, in

the UK the reluctance of consumers to commit to expensive

machines (not

being sure they would ever really have a use for them) led them

to

prefer renting, and the rental market was pretty well tied up by

VHS:

Betamax was the system of choice for informed consumers, but

over a

period of years VHS came to dominate the market.

in

the UK the reluctance of consumers to commit to expensive

machines (not

being sure they would ever really have a use for them) led them

to

prefer renting, and the rental market was pretty well tied up by

VHS:

Betamax was the system of choice for informed consumers, but

over a

period of years VHS came to dominate the market.

The early machines were unfriendly to operate: like the first-generation VHS shown to right, both formats used piano keys to operate, and there was no remote control nor scanning (playing at a high speed so that you could still see where you were) - this meant that skipping the advertisements meant getting out of your chair, stopping, spooling forward by an amount you could only guess at, stopping, playing, and if you weren't in the right place doing it all again. Second-generation machines had wired remote controls: but domestic video recorders really came of age with Sony's C7, released in 1980.

This

was the first fully-featured VCR. It had infra-red remote

control,

scanning forwards and backwards, slow-motion and freeze-frame,

and

electronic tuning. Its picture quality was very good, and it was

well-made. It was also expensive at around £600; but its

facilities

gradually filtered down to the cheaper models on both formats.

This

was the first fully-featured VCR. It had infra-red remote

control,

scanning forwards and backwards, slow-motion and freeze-frame,

and

electronic tuning. Its picture quality was very good, and it was

well-made. It was also expensive at around £600; but its

facilities

gradually filtered down to the cheaper models on both formats.

Video recorders became more common in homes. For the first time the question 'did you see (name of programme)?' could be answered 'not yet'. People could go out and not miss a favourite programme (though football fans watching recordings of live matches had to be careful not to spoil their enjoyment by finding out the result before watching the tape). Another factor which contributed to the popularity of VCRs was the rise of video rental stores: though the quality was variable a family could settle down to watch a film for a fraction of the cost of a trip to the cinema.

At

this stage the sound track was carried on a narrow linear track

along

the edge of the tape, and was adequate at best; later models

introduced

'hi-fi' sound, recorded by another spinning head underneath

the magnetic image of the video on the tape: though there were

still

snags to it the quality was very much better, and could

handle

stereo when the NICAM transmissions were added to

ordinary TV signals.

At

this stage the sound track was carried on a narrow linear track

along

the edge of the tape, and was adequate at best; later models

introduced

'hi-fi' sound, recorded by another spinning head underneath

the magnetic image of the video on the tape: though there were

still

snags to it the quality was very much better, and could

handle

stereo when the NICAM transmissions were added to

ordinary TV signals.

Sony's SL-HF950 (right) was hifi (though not with NICAM), and also the most complicated VCR ever available for domestic use, with complex editing facilities, and also the option of 'Super-Beta' which used a higher-quality tape to improve the picture sharpness: it was the swan-song of Betamax, which gradually fell out of use. VHS had much improved, and with the introduction of 'Super-VHS'

(S-VHS)

which again used higher-quality tape and produced

remarkably

sharp

pictures for a domestic device, the system was able to offer

extremely

good quality (though most people stuck to plain VHS). JVC's

HR-S5000

(left) was one of the first of this type and included NICAM

reception;

subsequent models introduced

digital video noise reduction, making a marked further

improvement in

the quality and taking tape recording about as far as it could

go.

'Super-VHS'

(S-VHS)

which again used higher-quality tape and produced

remarkably

sharp

pictures for a domestic device, the system was able to offer

extremely

good quality (though most people stuck to plain VHS). JVC's

HR-S5000

(left) was one of the first of this type and included NICAM

reception;

subsequent models introduced

digital video noise reduction, making a marked further

improvement in

the quality and taking tape recording about as far as it could

go.

Philips

made a late entry with their

V2000

system in 1979, which had interesting features like dynamic head

tracking for easy usability and improved still-frame and

slow-motion,

and recorded four hours on a cassette which could be turned over

to

record another four hours: but it had no hi-fi sound, and never

sold in

any

great quantity. Sony introduced a miniaturized system using 8mm

tape in

1985, but though some recorders were made it never caught on,

however

it became a standard for some years for domestic camcorders

where the

small size was an advantage.

Philips

made a late entry with their

V2000

system in 1979, which had interesting features like dynamic head

tracking for easy usability and improved still-frame and

slow-motion,

and recorded four hours on a cassette which could be turned over

to

record another four hours: but it had no hi-fi sound, and never

sold in

any

great quantity. Sony introduced a miniaturized system using 8mm

tape in

1985, but though some recorders were made it never caught on,

however

it became a standard for some years for domestic camcorders

where the

small size was an advantage.

Setting a VCR's timer involved entering the start and finish times, and the channel, and this foxed a lot of people (parents would often get their children to do it); early attempts to get round this included a large sheet of barcodes which could selected and scanned into the machine: this never really caught on. VideoPlus was a code number published in the schedules, which could be entered into a suitable equipped machine and would set all the recording details in one go: later this was combined with 'PDC' (Programme Delivery Control) where the broadcaster would send out a signal to tell the machine to start and stop at the exact times the programme was broadcast, thus handling late starts and over-runs. This was a good idea, but was mishandled so many times by the broadcasters that I for one gave up on it and returned to allowing a reasonable over-run and manual setting.

However tape was about to be overtaken by digital video recording, and this will be examined on the next page

1 BROADCAST VIDEO RECORDING

2 DOMESTIC VIDEO RECORDING (ANALOGUE)

3 DOMESTIC VIDEO RECORDING (DIGITAL)

Until the 1970s, television viewing was live: if you wanted to see a programme you had to arrange to be by a television when it was transmitted. Domestic video recording was a long wished-for facility, but though professional video recording had been around since 1958 it was phenomenally expensive and bulky (the Ampex machines cost a quarter of a million pounds each at 1960 prices).

The

earliest attempt to

create a domestic video

recorder was as far

back as 1963: Telcan (right) was a television

with an open-reel

recorder

mounted on top, using linear recording running ¼ inch tape at

120

inches/second for a maximum

running time of 15 minutes.

The

earliest attempt to

create a domestic video

recorder was as far

back as 1963: Telcan (right) was a television

with an open-reel

recorder

mounted on top, using linear recording running ¼ inch tape at

120

inches/second for a maximum

running time of 15 minutes.  There

was no timer, so you had to be there

anyway to record something: the quality was poor, and it was

unreliable, so it's not surprising that it didn't make any

headway. By

the late 1960s various open-reel video recorders using ½ inch

tape and

rotating heads were available, of which one of the most common

makes

was Shibaden

(left): again, there was no timer, and the cost and difficulty

of

lacing it up meant that it wasn't suitable for the domestic

market

(though it was useful for semi-professionals); the quality was

fairly

good but the tape was expensive. (A friend of mine had a couple

and

used cheaply-bought second-hand computer tape - the quality was

just

about watchable but not pretty).

There

was no timer, so you had to be there

anyway to record something: the quality was poor, and it was

unreliable, so it's not surprising that it didn't make any

headway. By

the late 1960s various open-reel video recorders using ½ inch

tape and

rotating heads were available, of which one of the most common

makes

was Shibaden

(left): again, there was no timer, and the cost and difficulty

of

lacing it up meant that it wasn't suitable for the domestic

market

(though it was useful for semi-professionals); the quality was

fairly

good but the tape was expensive. (A friend of mine had a couple

and

used cheaply-bought second-hand computer tape - the quality was

just

about watchable but not pretty). The

first successful domestic video recorder was the Philips

N1500 (right),

available from 1970 (1972 in the UK). It used tape in a

cassette, so

lacing up wasn't a problem; in order to acommodate the slanted

path

round the head drum the reels were placed one above the other in

the

cassette, which was roughly cubical in shape. The machine had a

primive

mechanical timer, so it would make unattended recordings, and

the

quality was quite acceptable. However the mechanical lace-up

round the

complicated tape path was liable to damage the tape; and the

machine

was quite expensive at £400 (and so was the tape); it was never

widely

bought, though well-off enthusiasts bought enough to make later

improved versions worth manufacturing.

The

first successful domestic video recorder was the Philips

N1500 (right),

available from 1970 (1972 in the UK). It used tape in a

cassette, so

lacing up wasn't a problem; in order to acommodate the slanted

path

round the head drum the reels were placed one above the other in

the

cassette, which was roughly cubical in shape. The machine had a

primive

mechanical timer, so it would make unattended recordings, and

the

quality was quite acceptable. However the mechanical lace-up

round the

complicated tape path was liable to damage the tape; and the

machine

was quite expensive at £400 (and so was the tape); it was never

widely

bought, though well-off enthusiasts bought enough to make later

improved versions worth manufacturing.In 1971 Sony introduced the U-matic video cassette recorder: it was aimed at the professional market and far too expensive for domestic use, but it paved the way for future developments: the tape was enclosed in a fairly bulky cassette, but with the spools on the same level, the slanted wrap round the head drum being achieved by placing the drum at a slight angle. This made the lacing process much easier and more reliable.

The

machine became an industry standard for some years for making

copies

for viewing or testing television recordings, but was far too

expensive

for domestic use. However in 1975 Sony released a scaled-down

and

simplified machine called 'Betamax'. The

cassettes

(left) used

½

inch tape, were a more manageable size, and ran for 3¼ hours;

there was

a digital timer which could also select the TV channel, so that

successive recordings from different channels became possible.

The

machine became an industry standard for some years for making

copies

for viewing or testing television recordings, but was far too

expensive

for domestic use. However in 1975 Sony released a scaled-down

and

simplified machine called 'Betamax'. The

cassettes

(left) used

½

inch tape, were a more manageable size, and ran for 3¼ hours;

there was

a digital timer which could also select the TV channel, so that

successive recordings from different channels became possible.JVC introduced a rival version called VHS ('Video Home System') which worked on basically the same principles, though with differences in the mechanics of the lace-up and the way the tracks were placed on the tape (in particular the machine unlaced every time it was stopped, whereas Betamax kept the tape laced until it was ejected). The cassettes ran for 3 hours (longer in the USA because of the different picture standards). The quality was inferior to Betamax, but while in the USA Betamax was the preferred domestic system for some years,

in

the UK the reluctance of consumers to commit to expensive

machines (not

being sure they would ever really have a use for them) led them

to

prefer renting, and the rental market was pretty well tied up by

VHS:

Betamax was the system of choice for informed consumers, but

over a

period of years VHS came to dominate the market.

in

the UK the reluctance of consumers to commit to expensive

machines (not

being sure they would ever really have a use for them) led them

to

prefer renting, and the rental market was pretty well tied up by

VHS:

Betamax was the system of choice for informed consumers, but

over a

period of years VHS came to dominate the market.The early machines were unfriendly to operate: like the first-generation VHS shown to right, both formats used piano keys to operate, and there was no remote control nor scanning (playing at a high speed so that you could still see where you were) - this meant that skipping the advertisements meant getting out of your chair, stopping, spooling forward by an amount you could only guess at, stopping, playing, and if you weren't in the right place doing it all again. Second-generation machines had wired remote controls: but domestic video recorders really came of age with Sony's C7, released in 1980.

This

was the first fully-featured VCR. It had infra-red remote

control,

scanning forwards and backwards, slow-motion and freeze-frame,

and

electronic tuning. Its picture quality was very good, and it was

well-made. It was also expensive at around £600; but its

facilities

gradually filtered down to the cheaper models on both formats.

This

was the first fully-featured VCR. It had infra-red remote

control,

scanning forwards and backwards, slow-motion and freeze-frame,

and

electronic tuning. Its picture quality was very good, and it was

well-made. It was also expensive at around £600; but its

facilities

gradually filtered down to the cheaper models on both formats.Video recorders became more common in homes. For the first time the question 'did you see (name of programme)?' could be answered 'not yet'. People could go out and not miss a favourite programme (though football fans watching recordings of live matches had to be careful not to spoil their enjoyment by finding out the result before watching the tape). Another factor which contributed to the popularity of VCRs was the rise of video rental stores: though the quality was variable a family could settle down to watch a film for a fraction of the cost of a trip to the cinema.

At

this stage the sound track was carried on a narrow linear track

along

the edge of the tape, and was adequate at best; later models

introduced

'hi-fi' sound, recorded by another spinning head underneath

the magnetic image of the video on the tape: though there were

still

snags to it the quality was very much better, and could

handle

stereo when the NICAM transmissions were added to

ordinary TV signals.

At

this stage the sound track was carried on a narrow linear track

along

the edge of the tape, and was adequate at best; later models

introduced

'hi-fi' sound, recorded by another spinning head underneath

the magnetic image of the video on the tape: though there were

still

snags to it the quality was very much better, and could

handle

stereo when the NICAM transmissions were added to

ordinary TV signals.Sony's SL-HF950 (right) was hifi (though not with NICAM), and also the most complicated VCR ever available for domestic use, with complex editing facilities, and also the option of 'Super-Beta' which used a higher-quality tape to improve the picture sharpness: it was the swan-song of Betamax, which gradually fell out of use. VHS had much improved, and with the introduction of

'Super-VHS'

(S-VHS)

which again used higher-quality tape and produced

remarkably

sharp

pictures for a domestic device, the system was able to offer

extremely

good quality (though most people stuck to plain VHS). JVC's

HR-S5000

(left) was one of the first of this type and included NICAM

reception;

subsequent models introduced

digital video noise reduction, making a marked further

improvement in

the quality and taking tape recording about as far as it could

go.

'Super-VHS'

(S-VHS)

which again used higher-quality tape and produced

remarkably

sharp

pictures for a domestic device, the system was able to offer

extremely

good quality (though most people stuck to plain VHS). JVC's

HR-S5000

(left) was one of the first of this type and included NICAM

reception;

subsequent models introduced

digital video noise reduction, making a marked further

improvement in

the quality and taking tape recording about as far as it could

go. Philips

made a late entry with their

V2000

system in 1979, which had interesting features like dynamic head

tracking for easy usability and improved still-frame and

slow-motion,

and recorded four hours on a cassette which could be turned over

to

record another four hours: but it had no hi-fi sound, and never

sold in

any

great quantity. Sony introduced a miniaturized system using 8mm

tape in

1985, but though some recorders were made it never caught on,

however

it became a standard for some years for domestic camcorders

where the

small size was an advantage.

Philips

made a late entry with their

V2000

system in 1979, which had interesting features like dynamic head

tracking for easy usability and improved still-frame and

slow-motion,

and recorded four hours on a cassette which could be turned over

to

record another four hours: but it had no hi-fi sound, and never

sold in

any

great quantity. Sony introduced a miniaturized system using 8mm

tape in

1985, but though some recorders were made it never caught on,

however

it became a standard for some years for domestic camcorders

where the

small size was an advantage.Setting a VCR's timer involved entering the start and finish times, and the channel, and this foxed a lot of people (parents would often get their children to do it); early attempts to get round this included a large sheet of barcodes which could selected and scanned into the machine: this never really caught on. VideoPlus was a code number published in the schedules, which could be entered into a suitable equipped machine and would set all the recording details in one go: later this was combined with 'PDC' (Programme Delivery Control) where the broadcaster would send out a signal to tell the machine to start and stop at the exact times the programme was broadcast, thus handling late starts and over-runs. This was a good idea, but was mishandled so many times by the broadcasters that I for one gave up on it and returned to allowing a reasonable over-run and manual setting.

However tape was about to be overtaken by digital video recording, and this will be examined on the next page