Wed - May 5, 2010Blog's endReturning to the weblog: I've posted all the anecdotes from my BBC career I can think of (at least those which aren't libellous), I've reviewed numerous concerts, and put up a number of photos and a few recordings. With the concert season coming to an end (nothing much happens over the summer unless you feel like trekking over to the Royal Albert Hall for the Proms) and nothing more in that line booked until late September, I think that I should quit while I'm ahead (if I am). I shall leave the entire blog up for the time being - people do come to some of the entries via Google (the 1935 photo of the Afsluitdijk in Holland seems popular for some reason). My thanks to the handful of people who have subscribed or followed it to some extent; I hope it's been entertaining. Posted at 10:24 AM by Roger Wilmut | Thu - April 29, 2010Prokofiev and MyaskovskyThe revised description was on account of the orchestra's expanded rôle, but in fact it didn't strike me as being unusually dominant - certainly less so than in Brahm's Second Piano Concerto, with its extended cello solo. The work manages to be both lyrical and spiky, with a good deal of the cello part being in an extremely high register, and very demanding on the player: Ishizaka gave an exciting and involved performance (breaking a string in the second movement, which caused a few minutes pause while he went off-stage and replaced it - a rare but not unusual event). Nikolai Myaskovsky's music is very rarely heard: his Sixth Symphony was composed in 1921-3 and is a massive work, running just over an hour and involving a large orchestra and an optional choir in the last movement (present in this performance). The dramatic tone of much of the work was apparently inspired in part by the death of the composer's aunt at the time he began composition; the first movement makes much use of dark-toned repetitive phrases in the lower strings, leading to strong brass chords and a sense of urgency: the second is a demonic scherzo, and the third slow and sadly lyrical: the music is often of indeterminate tonality but still melodic. The final movement starts in a jolly mood, strongly reminiscent of an Italian carnival (though in fact based on two songs from the French revolution) but gradually becomes more agitated, with quotes from the Dies Irae (the most quoted phrase in musical history, and every composer's shorthand for death). The work's construction is rather unfocused, but it contains much atmospheric music and deserves to be heard more often. A recording of the concert (presumably minus the broken string) will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on May 5th. Posted at 09:11 AM by Roger Wilmut | Fri - April 23, 2010Silent WaterlooThe film was made in Germany and directed by Karl Grune: unsurprisingly it tells the story very much from the German viewpoint, concentrating on the Prussian Field Marshal Blücher (played by Otto Gebühr), who (having previously defeated Napoleon and caused his exile to Elba) is called out of retirement upon Napoleon's escape and return to France. Promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the Prussian Army, Blücher forms an alliance with the Duke of Wellington. Blücher's troops are initially defeated by Napoleon, to whom the French Marshal Ney has defected, but when Napoleon attacks Wellington at Waterloo it is the nick-of-time arrival of Blücher's troops which saves the day. Napoleon himself (played by Charles Vanel - essaying the part for the third time) remains a shadowy figure, with the film concentrating on Blücher's activities. Because the historical plot is fairly simple there is a sub-plot involving a female German spy (Wera Malinowskaja) who seduces an aide of Blücher's (Oskar Marion) to the distress of the latter's fiancée (Betty Bird) - this tends to over-dominate the second half of the film (which is already long at two-and-a-half hours) though it does provide some human interest and a little comic relief when the spy attempts to turn her charm on Blücher. The battles are spectacularly staged, though some of the hand-to-hand combat is not convincing (consisting, as all too often, of actors standing a safe distance apart banging each other's bayonets) and well photographed; and, the sub-plot aside, the film appears to stick reasonably closely to the historical facts. Gebühr's performance as Blücher is very effective - first seen from behind examining a horse's shoe, and shown as a warm-hearted and somewhat eccentric but decisive commander. Though Malinowskaja's performance tends to descend into eye-rolling, the other actors give good and not over-stated performances and the whole film stands up well. There are some innovative multiple-exposure shots (possibly inspired by Abel Gance's Napoleon) but these are kept to a minimum and the narrative is clear and well laid out. The film gained immeasurably from Davis's effective score and the excitement of a full orchestra. The only downside of this sort of performance is that there is inevitably a lot of light spillage from the music stand lights which reduces the contrast of the on-screen image - and the RFH's projector really could do with a stronger light source. Even so the print was of fine quality from a recent restoration: it's a little-known classic and well worth seeing. Posted at 09:25 AM by Roger Wilmut | Thu - April 15, 2010Familiar Dvořák, unfamiliar Verdi and StraussThe opener was the ballet music from Verdi's opera Otello. Verdi never wanted the opera to be interrupted by a ballet, but the patrons of the Paris Opera used to insist on one (and not in the first act, for the benefit of the fashionably late arrivals); so he composed a six-minute set of 'middle eastern' dances to be inserted in Act 3 as a welcome for the Venetian ambassador, who is about to witness the explosion of Otello's jealousy. Fortunately practicably no production ever includes the dances, so it's interesting to hear them: pleasant enough, and about as authentic as Ballet Egyptien. Dvořák's Cello Concerto, on the other hand, is one of the most popular works in the repertoire: it single-handedly established the cello as a solo instrument where previously it had been regarded as unsuitable. It's a gift to the soloist - lyrical, evocative of the composer's native Bohemian countryside, and with an emotional sweep which can hold an audience spellbound. The soloist was Enrico Dindo: I found his tone a little too quiet, and managing to be both slightly muffled and feathery at the same time, but there was no mistaking his commitment to this enjoyable work. A rarely-heard tone poem by Richard Strauss to finish with: Aus Italien celebrates Italy in the same way (though perhaps less memorably) that he celebrated the Alpine landscape in the Alpensinfonie. Beginning with a quiet exploration of the Capagna region, the music becomes sunnier with its representation of the ruins of ancient Rome and the beach at Sorrento, finishing with a lively festival in Naples - the main theme of which is a version of the well-known Italian song Funiculi Funicula. The work as a whole is less well structured than most of Strauss's other tone poems, but exhibits his usual mastery of complex orchestration. Well worth hearing, and in an excellent performance. Posted at 09:14 AM by Roger Wilmut | Sun - April 4, 2010Secrets of a SoulDespite its fame, it's in fact more interesting for what it was than what it is - it seems rather slow and naïve now, but it was the first film to tackle Freudian analysis of dreams - at that time a fairly new concept to the general public. Later films such as Spellbound used the technique of interpretation of dreams, and their ability to retrieve buried memories which are causing mental illness, to drive a thriller plot: Secrets of a Soul examines a single case history and shows how the analysis uncovers the cause of a phobia. Though it's slow to unfold, and seems rather glib and easily solved, the illness was based on a real case, and considerable care seems to have been taken to stick to the medical facts: the subtitles stress that the process lasted many months, but inevitably cinematic storytelling tends to leave the impression that it all happened quite quickly.  The patient, played by Werner Krauss, has developed a phobia of knives

and razors, and find himself struggling with a desire to murder his wife by

stabbing, despite loving her. We see a dream he has - realised by clever use of

multiple exposures and distorting lenses - with disturbing and apparently

inexplicable images. He goes to a psychiatrist (Pawel

Pawlow): we see the dream again, in sections, as the psychiatrist

examines it and gradually uncovers the reasons - an unfulfilled desire for

children, an incident in his childhood, and so on - eventually effecting a

cure.

The patient, played by Werner Krauss, has developed a phobia of knives

and razors, and find himself struggling with a desire to murder his wife by

stabbing, despite loving her. We see a dream he has - realised by clever use of

multiple exposures and distorting lenses - with disturbing and apparently

inexplicable images. He goes to a psychiatrist (Pawel

Pawlow): we see the dream again, in sections, as the psychiatrist

examines it and gradually uncovers the reasons - an unfulfilled desire for

children, an incident in his childhood, and so on - eventually effecting a

cure.It's well done, though it does take a long time to establish the characters and show the development of the illness (preferable, though, to Hollywood's shorthand for mental illness - fingertips placed on the temple and a worried look, followed promptly by a full-scale breakdown) and the final idyllic scene in the countryside showing the couple with a baby is rather obviously tacked-on; it's an honest attempt to tackle a difficult and then little-understood process, and an important piece of cinema history. Posted at 07:13 PM by Roger Wilmut | Wed - March 31, 2010Three by MacMillanThe Judas Tree, to music by Brian Elias, is quite another matter; one of Macmillan's darker ballets (and his last) it was premiered in 1992, not long before his death. It's set on a building site near Canary Wharf (the tower is in the backdrop) as evening falls. The foreman brings his girlfriend and two male friends to the site; the girl is confident, teasing the men almost like a prostitute; the men show off to her. But it leads to gang rape, murder, and the hanging of one of the foreman's friends. There are connections to the Bible, with the foreman representing Judas, the girl Mary Magdelene and the hanged friend Jesus, but these are vague and I have to say the whole thing is unclear and despite some interesting choreography doesn't really come off. Well danced, though, particularly by Mara Galeazzi as the girl and Thiago Soares as the foreman. The final ballet was the lively Elite Syncopations in its first revival for 36 years. It's set to ragtime pieces by Scott Joplin and others; and onstage band plays in what seems to be a dance hall while brightly dressed dancers perform in various combinations. There are 'movement quotes' from long-forgotten dance crazes of the Edwardian era, and the choreography builds on the period flavour. I saw this with the original cast when it premiered in 1974; it was recorded by the BBC the following year (broadcast on 21 September 1975) and I saw this at the National Film Theatre in 2002, but it's a treat to see it live once more. You can see a few video excerpts from another production here, and one of the dances from an undientified production here.) The new cast, including Laura Morera, Yuhui Choe Thiago Soares and Ludovic Ondiviela stood up well to my memories of the stellar originals (who included Merle Park, Monica Mason, Michael Coleman and Jennifer Penney). There is a comic dance in which a bumbling and overeager - and small - male dancer pairs with a tall girl: Michael Stojko, complete with Harold Lloyd glasses, isn't quite as small as the original, the diminutive Wayne Sleep, but the dance is still hilarious. My only reservation is that there is rather a balance towards slower pieces, with the faster ones only at the beginning and end, and I could have done with perhaps one less slow one and one more faster one to keep the impetus up; but it's a colourful and entertaining ballet. Posted at 09:33 AM by Roger Wilmut | Thu - March 25, 2010Three Russian composersIn 1924 Prokofiev premiered a revised version of the work, reconstructed from his memory but with numerous revisions. It's impossible to know how much it differs from the original - it's been suggested that there is so much difference that it might as well be regarded as a new concerto: in the extremely unlikely event of the original ever turning up the musicologists will have a field day. The work is spiky and percussive, with an undertone of despair probably caused by the suicide of a close friend of the composer; it makes very extensive demands on the pianist - in this case 23-year-old Yuja Wang who has already made a considerable name for herself: it was slightly disconcerting to hear so much power and complexity from such a slight frame. It's not an easy work to appreciate, and despite having four movements there is a certain sameness to the approach through most of it; but well worth hearing and a fine performance. The second half of the concert consisted of a complete performance of Stravinsky's ballet The Firebird. Stravinsky was a pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov, and the ballet takes Rimsky-Korsakov's mastery of orchestration and adds the beginning of Stravinsky's own individual complexity to it. Prior to this Stravinsky had written a handful of pieces strongly influenced by Rimsky-Korsakov; with The Firebird he began an amazingly rapid progression, through the more sombre colours of Petrushka and the barbarity of The Rite of Spring - one of the key works bridging Romanticism and Modernism - and on into his fully matured and continually developing style. I have a couple of good recordings of the music, but no recording can compare with the experience of hearing the full detail of this very complex work in a live performance. Posted at 08:51 AM by Roger Wilmut | Wed - March 17, 2010Canon fodderI

Unfortunately

Hewlett-Packard (HP) have declined to update the driver for my Deskjet 990cxi

printer (right) which is now some years old: I suppose that one can't expect

older equipment to be supported for ever, but this is a good printer, and wasn't

cheap, so I'm not pleased to be effectively told by their website to go and buy

a new printer. Unfortunately

Hewlett-Packard (HP) have declined to update the driver for my Deskjet 990cxi

printer (right) which is now some years old: I suppose that one can't expect

older equipment to be supported for ever, but this is a good printer, and wasn't

cheap, so I'm not pleased to be effectively told by their website to go and buy

a new printer.Apple include an open-source driver called Gutenprint which will recognize the printer, but it won’t do the automatic double-sided printing, and the colour results aren’t quite as good - a block area of yellow has a lot of miniscule orange dots in it and no adjustment I've been able to find will remove them. There also a mechanical problem with the printer: the plastic clip holding the black cartridge in place has broken on one side: it still works, but if the other side breaks - as it will, sooner or later - the printer will probably become unusable (and it’s not possible to repair this). So I decided to buy a new printer rather than wait for the present one to fail: by rearranging some books I’ve managed to find room for both of them so I can keep the old one as a spare, as long as it still works.  After

some deliberation I bought a Canon ‘PIXMA’ IP4700 (left);

it’s an inkjet positioned as a photo printer; my HP, and a modern one by

them I looked at - the OfficeJet 8000 Pro (which is very large and

heavy) - are meant as office printers and tend to be more robust; but they

don’t do photos quite as well, and as I don’t do an awful lot of

printing the Canon should be fine. Some reviews of this felt that the paper

cassette was flimsy and difficult to insert, but I didn't find any difficulty

with it - the printer seems robust enough for domestic use though I wouldn't

recommend it for a busy office. After

some deliberation I bought a Canon ‘PIXMA’ IP4700 (left);

it’s an inkjet positioned as a photo printer; my HP, and a modern one by

them I looked at - the OfficeJet 8000 Pro (which is very large and

heavy) - are meant as office printers and tend to be more robust; but they

don’t do photos quite as well, and as I don’t do an awful lot of

printing the Canon should be fine. Some reviews of this felt that the paper

cassette was flimsy and difficult to insert, but I didn't find any difficulty

with it - the printer seems robust enough for domestic use though I wouldn't

recommend it for a busy office.On proper paper the photos results are excellent: the printer uses finer droplets than the HP, and has the three colours in separate cartridges rather than three colours in one; it also has two black cartridges, one for text and one for use in photos to give the blacks more solidity. The results are impressive: impossible to tell from a shop-made photo print. It’s quite fast, has automatic double-sided printing, and two paper holders - a cassette at the bottom for plain paper, and a holder at the rear for photo and odd-sized paper as well as plain. It lacks the HP's ability to auto-detect the type of paper in use, but it does have one trick the HP doesn’t; it will print on recordable CD or DVD labels (you have to use printable blank media, not just ordinary ones) - in the photo you can see the tray holding the CD, though as I don’t have any printable ones the CD in it is an ordinary one. It’s not a function I expect to make much use of, though. Posted at 09:20 AM by Roger Wilmut | Sat - March 13, 2010Early AliceIt was made by the Hepworth studio, and, together with many of their films, disappeared when the studio closed and was thought lost - a copy was discovered in the 1960s. It's missing four of the twelve minutes - mostly in small bits - and is in poor and damaged condition; but it gives a fascinating glimpse into cinema of the period. It's pretty well a home movie, with the parts being played by studio regulars (and Alice by the secretary) - the Cheshire cat is played by a real (and disgruntled-looking) cat. Of course it's amateurish and clunky, but a remarkable first effort. (You can see the entire film on YouTube).  The

main part of the programme was Paramount's starry 1933 version. It's certainly a stellar cast:

Gary Cooper as the White Knight, Cary Grant as the Mock Turtle, Edward Everett

Horton as the Mad Hatter, Edna May Oliver as the Red Queen, W.C.Fields as Humpty

Dumpty, an many more including Sterling Holloway as the Frog (he would later be

the voice of the Cheshire Cat in the Disney version). Alice was played by

Charlotte Henry - a little too old but quite

appealing. The

main part of the programme was Paramount's starry 1933 version. It's certainly a stellar cast:

Gary Cooper as the White Knight, Cary Grant as the Mock Turtle, Edward Everett

Horton as the Mad Hatter, Edna May Oliver as the Red Queen, W.C.Fields as Humpty

Dumpty, an many more including Sterling Holloway as the Frog (he would later be

the voice of the Cheshire Cat in the Disney version). Alice was played by

Charlotte Henry - a little too old but quite

appealing. A

lot of work has gone into making it look like the Tenniel illustrations; however

this involves heavy masks in many cases which render the stars unrecognizable -

they look rather stiff, and in several cases have no movement at all. Cooper,

Horton and Fields come off best, and the film benefits from most of the dialogue

having been lifted straight from the

books. A

lot of work has gone into making it look like the Tenniel illustrations; however

this involves heavy masks in many cases which render the stars unrecognizable -

they look rather stiff, and in several cases have no movement at all. Cooper,

Horton and Fields come off best, and the film benefits from most of the dialogue

having been lifted straight from the

books.As with most adaptations, episodes from Wonderland and Through The Looking-Glass are used: Alice starts by going through the mirror and encountering the chess pieces, then falls down the rabbit-hole: several episodes from the first book (including the croquet game but not the trial) are the followed by some from the second (including the final nightmarish feast), though the point of the chess game itself is rather lost. Carroll's dreamlike logic survives quite well, and there is an attractive score by Dmitri Tiomkin; the overall effect is quite enjoyable even though many of the performances are rather wooden. This film is very rarely shown - I don't think it's ever been on British television, but it is available on DVD (Region 1 only). I've not seen the Burton: I may watch it when it turns up on television, but as no-one seems to be able to tell the difference between the Red Queen and the Queen of Hearts I can't raise a lot of enthusiasm for the rest of it. Posted at 09:36 AM by Roger Wilmut | Wed - March 10, 2010Mozart, Schubert and a different conductorMozart's Sinfonia Concertante for violin, viola and orchestra in E flat, K364 is oddly named, because in effect it's a double concerto - three movements, not four. The soloists were Janin Jansen (violin) and Maxim Rysanov (viola). The work is one of Mozart's finest, the slow movement in particular having easy-flowing melodic lines and a depth of feeling which placed him well ahead of his times. Since E flat is an awkward key for the viola Mozart specified that the instrument should be tuned a semitone sharp and composed the part in D major: one wonders how a violist with perfect pitch would cope (and how many strings get broken in the process). The young soloists played well together, though Jansen's tone was a little thin and sometimes the viola overbalanced her; but on the whole their committed and warm playing brought out the best in this marvellous work. Schubert never heard his 9th (and last) Symphony ('The Great'): his attempts to get it performed were rejected on the grounds of it being too difficult. Ten years after his death it finally received a performance under Mendelssohn's direction - though in a cut version: it runs 50 minutes and this was felt to be too exhausting for the players. Modern orchestras evidently have more stamina - and after Mahler 50 minutes doesn't seem excessive. The work maintains its length well, with plenty of invention and development; after a solemn (and yesterday perhaps a little ponderous) opening the first movement has a strong drive and memorable melodies. The slow movement is a moderately-speeded and restrained march, the scherzo is a lively rustic waltz and the finale - here played with with excitement and precision - a fast tarantella. A complex, lively and mature work and - despite the unexpected hand at the tiller - a splendid performance. Posted at 09:12 AM by Roger Wilmut | Wed - March 3, 2010Czech chamber musicNext came the first four of Dvořák's 'Cypresses' - arrangements of songs he had composed earlier, and with more depth than one might have expected from the source. The first half ended with Janáček's String Quartet No.1, nicknamed 'The Kreutzer Sonata' after the novel by Tolstoy which inspired it - itself taking its title from the Beethoven Sonata of that name. Janáček's music is a sharp contrast to Dvořák's - a muted start, and then often spiky, with much use of 'sul pont' - where the violinist uses the bow close to the bridge, producing a thin, edgy sound. The second half consisted of Dvořák's Piano Quintet No.2, for which the quartet was joined by pianist Menahem Pressler. This again showed Dvořák's gift for melody and Czech atmosphere, with a flowing and gentle first movement, and a final movement with a rapid and lively dance tune in gypsy style. All well played by the Quartet and much appreciated by the audience. Posted at 08:54 AM by Roger Wilmut | Sun - February 21, 2010Janáček and SukLeoš Janáček is of course well known, particularly for his operas such as Jenůfa, Káťa Kabanová and Věc Makropulos. The concert opened with two of his shorter works: Taras Bulba and The Eternal Gospel. The former is based on a novel by Gogol - also the subject of an opera and several films (including a Hollywood one with Yul Brynner and Tony Curtis) - which tells the violent sorty of a Ukranian Cossack and his struggles against the occupying and tyrannical Poles. Janáček's tone poem is suitably dramatic, in his characteristic plangent style. The Eternal Gospel (Věčné evangelium) is a short cantata for chorus, orchestra and two soloists. The advertised tenor was ill, and replaced at very short notice by Adrian Thompson, who gave no indication of any uncertainty or lack of rehearsal (and the part isn't easy, and in Czech to boot). It's an effective and individual work, leading to Janáček's later full-length Glagolitic Mass. Josef Suk (1874-1935) isn't well known in the UK (though his violinist grandson of the same name was fairly well known in the 1970s from his Supraphon records): he composed many works in Czech Romantic style. He was strongly influenced by Dvořák and also married Dvořák's daughter, and was much distressed by Dvořák's death in 1904: while composing an extended work inspired by this event his wife died suddenly. The resultant work, the Asrael Symphony (Azrael is the traditional name of the Archangel of Death) flows from Suk's grief: despite its origins it's not a gloomy work, though it does work through grief and fear, only reaching a calm conclusion at the very end. Running for an hour, it's complex and detailed, with rich orchestration. It's very rarely played, though there are a couple of recordings around (one a SACD), but well worth hearing. It can't be easy to lead the work through its long path but Jurowski handled it magnificently, as did the orchestra. Suk himself said about writing the symphony, 'music saved me'. A recording of this concert is being broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on Wednesday February 24th at 7.30 PM, and will be available on the 'iPlayer' for 7 days thereafter. Posted at 10:53 AM by Roger Wilmut | Mon - February 15, 2010Three from BollywoodSo I thought I'd give three of these films a go: with reservations, they proved worth seeing. Om Shanti Om (2007) is pitched as a musical, with a good deal of comedy even though the underlying plot is melodramatic. A bit-part performer in 1970s Bollywood, Om (Shahrikh Khan) falls in love with an established film star Shanti (Deepika Padukone): however she is secretly married to the film's slimy producer (Arjun Rampal). He wants to keep the marriage secret for career reasons: when she demands to have it recognized he kills her, and also Om who witnesses the murder. Thirty years later he been resurrected as a successful film star: only eventuallly remembering his former life he finds an actress with a strong resemblence to Shanti with the hope of scaring the producer into a confession: but during their attempt Shanti's ghost appears and kills him in revenge. The film is fun, though you don't have to take the melodramatic plot too seriously (and it makes little sense), and the songs and music fit into it well. There are some amusinc digs at 1970s Bollywood, including placing Shanti into scenes from some old films. The second film, Rang de Basanti (The Colour of Sacrifice) (2006) is a more serious affair. British documentary film-maker Sue (Alice Patten) is intrigued by the diary of British officer in 1940s India who oversaw the jailing and hanging of several young Indian men for being freedom fighters against British rule. Refused permission by her company to make a film about it she goes to India anyway and with the help of a friend recruits several young men to act in her film. They are young, irresponsible and mostly interested in chasing girls, but gradually get caught up in the drama of the story. Tensions mount when a Muslim joins the otherwise Hindi cast: then a friend who flies MiG fighter planes for the government is killed in a crash which is attributed to poor maintenance - itself caused by government corruption. Incensed by this, and inspired by the characters they have been acting, they assassinate the Minister responsible and hijack a radio station to broadcast their reasons: they are killed by the security forces. A caption tells us that though this is fiction, many pilots have been killed in MiG crashes. The drama is well played out, involving us as the comedy slowly turns to drama and tragedy: but the obligatory songs and dances are spatchcocked into the plot and merely distract from it: the film would be much stronger and more effective without them. However it's certainly produced an effect in India, spurring protests about corruption and being itself none too popular with the authorities.  From

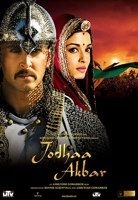

comedy and serious drama to overblown historical epic. Jodhaa

Akbar (2008) is based very loosely on a real Mughal emperor of the

sixteenth century, though most of the plot is fiction. Emperor Akbar (Hrithik

Roshan) has conquered most of the kingdoms over a wide area. To cement this rule

over the Rajputs he marries the King's daughter, Jodhaa (Aishwarya Rai) over her

opposition. Though they are hostile to each other at first, their love slowly

develops, and this is the main plot of the film through a welter of subplots

involving battles, treason, revenge and

duels. From

comedy and serious drama to overblown historical epic. Jodhaa

Akbar (2008) is based very loosely on a real Mughal emperor of the

sixteenth century, though most of the plot is fiction. Emperor Akbar (Hrithik

Roshan) has conquered most of the kingdoms over a wide area. To cement this rule

over the Rajputs he marries the King's daughter, Jodhaa (Aishwarya Rai) over her

opposition. Though they are hostile to each other at first, their love slowly

develops, and this is the main plot of the film through a welter of subplots

involving battles, treason, revenge and

duels.The film has caused controversy: present-day Rajputs objected to the portrayal of their ancestors (who I would have thought come out of the story quite well, even though one of them is the main villain), and there have been objections about historical accuracy (Jodhaa may actually have been married to Akbar's son) which seem a bit off the point - it's on a par with Robin Hood: a colourful legend, not a history lesson. Though Roshan is a little bland, Rai is genuinely beautiful and acts the character convincingly; and the other actors manage the grand manner without turning it into ham. The inevitable songs and dances - with a huge number of dancers - jar less than they might in what is hardly an accurate representation of history: and the photography is stunning. It's a tribute to the film-maker's skill that it sustains what is really a very slight plot through three hours and twenty minutes (though I was watching it in a comfortable armchair with breaks when required: I would have been less happy about it in a cinema with no interval). It deserves to be on Blu-Ray - it isn't yet, but there is an apparently none-too-good DVD transfer - though I'm not entirely sure it would stand up to repeated viewing. Well worth seeing once, though, in the best quality you can find. Just get a comfortable chair. Posted at 10:41 AM by Roger Wilmut | Tue - February 9, 2010The Czech National Symphony OrchestraHe was not, however, supported as well as he might have been by the orchestra: there was a slightly sour tone to the woodwinds - almost like being very slightly off-tune, though I don't think they actually were: it's more a remnant of the pawky quality that used to be common in Eastern European orchestras and may have been as much down to the tone of the oboe as anything else: the woodwind section never really gelled. Add to that a tendency for the horns to blare, and a slightly wooden perfomance overall, and the concerto, though enjoyable enough, never really soared as it should have done. The second half began with Hummel's Trumpet concerto, with soloist Jan Hasenohrl: one doesn't hear so much of Hummel these days, and though he was born in Bratislava in 1778, in what was then part of the Hungarian Empire and later became Czechoslovakia, his music is firmly rooted in the German tradition. The first two movements are strongly influenced by Mozart, though fairly unmemorable: the last is more fun, a lively Galop placing very considerable demands on the soloist, and well played. The concert ended with Dvořák's Symphony No. 8; the opening movement went well enough - the orchestra does forceful better than it does lyrical - but the second, slow, movement was rather dull and the third, more lively, movement rather plodding. The Elgarian opening to the final movement was suitably dramatic, and the final accelerated section caught fire much better than the the preceding sections. Overall it was quite enjoyable (and much appreciated by the audience) but the very high quality of the leading orchestras one normally hears does throw even slightly less skilled playing into relief. Posted at 10:57 AM by Roger Wilmut | Wed - February 3, 2010Broadcasting history The site is at http://wilmut.uk/broadcast Posted at 09:35 AM by Roger Wilmut | Fri - January 29, 2010Elgar and ManfredThe second part of the concert consisted of Tchaikovsky's Manfred: it's described as a 'Symphony in four scenes after Byron' and is somewhere between a symphony and a tone-poem: it was never given a number to list it with his other symphonies, and has never been as well-known. It's based on a poem by Byron: Manfred, living alone in the Alps and tortured by his incestuous love for his sister Astarte, has magical knowledge: but though he raises the spirits of hell he cannot gain the oblivion he seeks. Tchaikovsky expanded the idea to include a couple of lighter middle movements: a vision of an Alpine fairy who appears to Manfred but cannot help him, and a representation of the simple peasant life from which Manfred is forever barred. After a dramatic first movement, representing Manfred's desperation, the middle two movements come as attractive lighter relief. In the final movment the denizons of Hell perform a satanic dance (actually in Tchaikovsky's music they sound rather a jolly lot): in the interests of what Hollywood calls 'closure' Tchaikovsky departs from Byron - who condemned his anti-hero to eternal damnation - in having the ghost of Astarte forgive her brother, who can then find a peaceful death. The music is suitably forceful and dramatically orchestrated, with some of the best of Tchaikovsky's melodic gift: and peformed with fire and conviction by the orchestra. Posted at 09:37 AM by Roger Wilmut | Entries 2006-7 | May-Dec 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

MY PODCAST

Archives

Calendar

Blogroll

WEBRINGS

Statistics

Published On: Mar 11, 2016 05:01 PM |

||||||||||||||||||