CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION

2 STEEL TAPE

3 OPTICAL FILM

4 DIRECTLY-CUT DISKS

5 MAGNETIC TAPE

6 PORTABLE RECORDING

7 CARTS AND DARTS

8 DIGITAL RECORDING AND PLAYOUT

Cinema films

were made with sound from the end of the 1920s; disk and optical

recording ran side-by-side for a time, but the advantages of optical

were considerable, particularly in editing, and in that the track was

on the projection print alongside the picture and so couldn't get lost

or out of synchronization. Though the quality could be noisy at first,

it was rapidly improved.

Cinema films

were made with sound from the end of the 1920s; disk and optical

recording ran side-by-side for a time, but the advantages of optical

were considerable, particularly in editing, and in that the track was

on the projection print alongside the picture and so couldn't get lost

or out of synchronization. Though the quality could be noisy at first,

it was rapidly improved.

There were a few stand-alone optical recorders, such as the Selenophone which used 35mm film sliced to leave just the sound-track and adjacent sprockets, and was used for recording the 1937 Salzburg Festival opera performances (not by the BBC). However the system was not really suitable for broadcasting as the film had to be developed, causing delays, and the quality was mediocre.

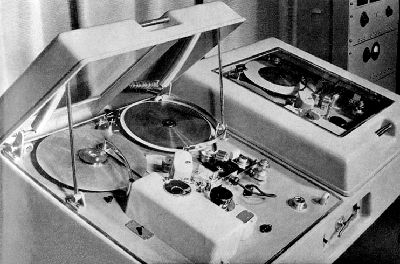

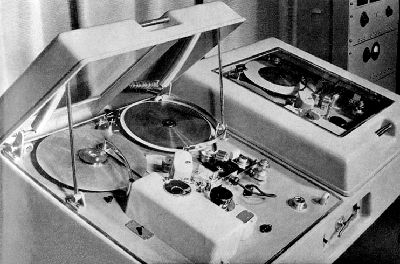

The BBC became interested

in a development by the Dutch Philips company, the Philips-Miller

optical recorder. Instead of using photographic techniques, this used

film stock coated with a clear layer of gelatine with a thin opaque

covering. A stylus with a wide angle moved vertically and cut away the

opaque layer to make a variable-area soundtrack; this could be played

back immediately using a light beam and a photoelectric cell (the same

as for a photo-optical recording). The film travelled at 32 cm/second

(fractionally over 12½ inches/second).

The BBC became interested

in a development by the Dutch Philips company, the Philips-Miller

optical recorder. Instead of using photographic techniques, this used

film stock coated with a clear layer of gelatine with a thin opaque

covering. A stylus with a wide angle moved vertically and cut away the

opaque layer to make a variable-area soundtrack; this could be played

back immediately using a light beam and a photoelectric cell (the same

as for a photo-optical recording). The film travelled at 32 cm/second

(fractionally over 12½ inches/second).

Both

the machines and the reels of film were a much more practicable size

than the Marconi-Stille, the film could be easily edited (using film

cement, as with cinema film), and though there was still some

background noise the quality was quite good. The BBC started

experimenting with this system in 1935 and it gradually came into use.

Both

the machines and the reels of film were a much more practicable size

than the Marconi-Stille, the film could be easily edited (using film

cement, as with cinema film), and though there was still some

background noise the quality was quite good. The BBC started

experimenting with this system in 1935 and it gradually came into use.

With the onset of the war in 1939 the ability to make recordings suddenly became much more important. The concept of a programme appearing on the same day of the week became normal for the first time, because of the expected difficulty in distributing the Radio Times. Programmes such as the immensely popular ITMA were performed live but recorded on Philips-Miller for subsequent repeat - up to then Variety and similar programmes had not normally been repeated, and with the difficulties caused by the war a second chance to hear a programme became important.

There were difficulties in obtaining the film stock during wartime, and two methods were used to eke it out - programmes where a lower quality could be accepted were recorded at 20 cm/sec; and there was enough space to record two tracks (separately) side-by-side. I believe some were even made with three, though this would pose a danger of peaks on one track breaking through into the adjacent one (and I've heard something suspiciously like this on recordings).

The surviving wartime ITMAs were all recorded on (and have since been transferred from) Philips-Miller, as was the very ambitious Louis MacNeice play Christopher Columbus, performed live in 1942 and involving multiple studios, a huge cast, a chorus and the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Though reasonably reliable the machines did require skilled handling; because the cutting stylus had to be exactly made, when engineers found one that worked well they tended to appropriate it and carry it for their own use. The system continued through into the post-war period but fell out of use by the end of the 1940s.

At the same time as the Philips-Miller was coming into use, a new method of disk recording was developed, and this will be covered on the next page.

1 INTRODUCTION

2 STEEL TAPE

3 OPTICAL FILM

4 DIRECTLY-CUT DISKS

5 MAGNETIC TAPE

6 PORTABLE RECORDING

7 CARTS AND DARTS

8 DIGITAL RECORDING AND PLAYOUT

Cinema films

were made with sound from the end of the 1920s; disk and optical

recording ran side-by-side for a time, but the advantages of optical

were considerable, particularly in editing, and in that the track was

on the projection print alongside the picture and so couldn't get lost

or out of synchronization. Though the quality could be noisy at first,

it was rapidly improved.

Cinema films

were made with sound from the end of the 1920s; disk and optical

recording ran side-by-side for a time, but the advantages of optical

were considerable, particularly in editing, and in that the track was

on the projection print alongside the picture and so couldn't get lost

or out of synchronization. Though the quality could be noisy at first,

it was rapidly improved.There were a few stand-alone optical recorders, such as the Selenophone which used 35mm film sliced to leave just the sound-track and adjacent sprockets, and was used for recording the 1937 Salzburg Festival opera performances (not by the BBC). However the system was not really suitable for broadcasting as the film had to be developed, causing delays, and the quality was mediocre.

The BBC became interested

in a development by the Dutch Philips company, the Philips-Miller

optical recorder. Instead of using photographic techniques, this used

film stock coated with a clear layer of gelatine with a thin opaque

covering. A stylus with a wide angle moved vertically and cut away the

opaque layer to make a variable-area soundtrack; this could be played

back immediately using a light beam and a photoelectric cell (the same

as for a photo-optical recording). The film travelled at 32 cm/second

(fractionally over 12½ inches/second).

The BBC became interested

in a development by the Dutch Philips company, the Philips-Miller

optical recorder. Instead of using photographic techniques, this used

film stock coated with a clear layer of gelatine with a thin opaque

covering. A stylus with a wide angle moved vertically and cut away the

opaque layer to make a variable-area soundtrack; this could be played

back immediately using a light beam and a photoelectric cell (the same

as for a photo-optical recording). The film travelled at 32 cm/second

(fractionally over 12½ inches/second). Both

the machines and the reels of film were a much more practicable size

than the Marconi-Stille, the film could be easily edited (using film

cement, as with cinema film), and though there was still some

background noise the quality was quite good. The BBC started

experimenting with this system in 1935 and it gradually came into use.

Both

the machines and the reels of film were a much more practicable size

than the Marconi-Stille, the film could be easily edited (using film

cement, as with cinema film), and though there was still some

background noise the quality was quite good. The BBC started

experimenting with this system in 1935 and it gradually came into use.With the onset of the war in 1939 the ability to make recordings suddenly became much more important. The concept of a programme appearing on the same day of the week became normal for the first time, because of the expected difficulty in distributing the Radio Times. Programmes such as the immensely popular ITMA were performed live but recorded on Philips-Miller for subsequent repeat - up to then Variety and similar programmes had not normally been repeated, and with the difficulties caused by the war a second chance to hear a programme became important.

There were difficulties in obtaining the film stock during wartime, and two methods were used to eke it out - programmes where a lower quality could be accepted were recorded at 20 cm/sec; and there was enough space to record two tracks (separately) side-by-side. I believe some were even made with three, though this would pose a danger of peaks on one track breaking through into the adjacent one (and I've heard something suspiciously like this on recordings).

The surviving wartime ITMAs were all recorded on (and have since been transferred from) Philips-Miller, as was the very ambitious Louis MacNeice play Christopher Columbus, performed live in 1942 and involving multiple studios, a huge cast, a chorus and the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Though reasonably reliable the machines did require skilled handling; because the cutting stylus had to be exactly made, when engineers found one that worked well they tended to appropriate it and carry it for their own use. The system continued through into the post-war period but fell out of use by the end of the 1940s.

At the same time as the Philips-Miller was coming into use, a new method of disk recording was developed, and this will be covered on the next page.