CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION

2 STEEL TAPE

3 OPTICAL FILM

4 DIRECTLY-CUT DISKS

5 MAGNETIC TAPE

6 PORTABLE RECORDING

7 CARTS AND DARTS

8 DIGITAL RECORDING AND PLAYOUT

While before the advent of magnetic tape it had been possible to do mobile recording - involving a car-full of equipment - the only portable recorder had been the BBC midget disk recorder, used by war correspondents - and that was no light weight. With tape it became possible to make much smaller and lighter devices, with the aim of allowing a single non-technical member of staff to go out and make a location recording such as an interview without involving a lot of complex equipment.

The

EMI Midget (left) was the first practicable device of this type

used by the BBC. Its size was 14 by 7 by 8 inches; initially

using valves (later versions were transistorized with consequent

savings on weight and battery usage) it recorded at 7½ips on

five-inch spools (holding 15 minutes): it had no erase head so

it was vital to use clean tape (more than one producer failed to

pay attention to this point and brought back an unusable

recording as a result).

The

EMI Midget (left) was the first practicable device of this type

used by the BBC. Its size was 14 by 7 by 8 inches; initially

using valves (later versions were transistorized with consequent

savings on weight and battery usage) it recorded at 7½ips on

five-inch spools (holding 15 minutes): it had no erase head so

it was vital to use clean tape (more than one producer failed to

pay attention to this point and brought back an unusable

recording as a result).

Two sets of batteries were required, nine dry cells lasting about 6 hours for 'low tension' (valve heaters) and motors, and two 67.5 dry batteries for the 'high tension' supply, lasting about 15 hours. The quality was very good, and the tapes - which were recorded full-track, as with studio machines - could be rewound onto larger spools for immediate editing or use in a studio.

This machine considerably increased the freedom of producers to obtain inserts such as interviews or background effects for features; but weighing in at 14½ lbs (6½kg) it was still quite a heavy object to carry any distance; so there was always a need for smaller high-quality machines.

The

Uher portable (right) became available in the early 1960s and

rapidly replaced the EMI as the machine of choice; it soon

became standard issue. It recorded on 5 inch reels at speeds

of 7½, 3¾, 17/8 and 15/16

ips, though obviously only 7½ was ever used by the BBC. It

recorded half-track, like domestic machines, so it was advisable

to use clean tape, and if both tracks of the tape were used it

would have to be specially dubbed on return to the studio (this

was before stereo: all studio machines were full track). The

quality was excellent, though it was alarming how many

producer-made recordings came back somewhat distorted.

The

Uher portable (right) became available in the early 1960s and

rapidly replaced the EMI as the machine of choice; it soon

became standard issue. It recorded on 5 inch reels at speeds

of 7½, 3¾, 17/8 and 15/16

ips, though obviously only 7½ was ever used by the BBC. It

recorded half-track, like domestic machines, so it was advisable

to use clean tape, and if both tracks of the tape were used it

would have to be specially dubbed on return to the studio (this

was before stereo: all studio machines were full track). The

quality was excellent, though it was alarming how many

producer-made recordings came back somewhat distorted.

A friend had his own Uher: on one occasion we were attempting to mimic the distorted sound of a producer-made recording for comic effect: we recorded so that the meter peaked well into the red overload area: and it sounded fine. So then we recorded with the meter never coming out of the red area: then it sounded like a producer-made recording.

The Uher was considerably lighter than the EMI at around 8lbs (3.6kg) but still heavy enough to make your shoulder ache if you carried it any distance; so there was always going to be a demand for really small machines. Unfortunately these tended to be domestic models with variable quality and poor reliability.

The

Fi-Cord (left) was marketed from 1959 for domestic use: it was

very small at 95/8 by 5 by

2¾ inches and weighed only 4½lbs (2kg). It used 3 inch spools

containing long play (1 thousandth of an inch thick) tape which

would run for eight minutes at 7½ips - the very thin tape needed

careful handling and had to be dubbed on return to base as it

couldn't be reliably edited or played in a studio. The quality

was capable of being very good, but the machine was touchy and

tricky to use. One producer brought me a tape which had been

laced with a small amount sticking out underneath the reel: this

had caused the machine to proceed in a series of jerks. He asked

if I could use the variable-speed unit to correct this...

The

Fi-Cord (left) was marketed from 1959 for domestic use: it was

very small at 95/8 by 5 by

2¾ inches and weighed only 4½lbs (2kg). It used 3 inch spools

containing long play (1 thousandth of an inch thick) tape which

would run for eight minutes at 7½ips - the very thin tape needed

careful handling and had to be dubbed on return to base as it

couldn't be reliably edited or played in a studio. The quality

was capable of being very good, but the machine was touchy and

tricky to use. One producer brought me a tape which had been

laced with a small amount sticking out underneath the reel: this

had caused the machine to proceed in a series of jerks. He asked

if I could use the variable-speed unit to correct this...

For

this sort of reason the Fi-Cord never really caught on and had

very little use. At the other end of the scale, for doing

high-quality recordings without the need for a carload of gear,

the Nagra (right) could be used, though as it was extremely

expensive an engineer was required to go along to operate it. It

was 14¼ by 9½ by 43/8

inches, and weighed almost 16lbs (so heavier even than the EMI

midget). It could record at 15 ips as well as 7½ and 3¾ ips on 7

inch reels, thus making it more suitable for music, and its very

high quality produced results well up to the standard of the

best studio machines. Obviously it was suitable only for special

occasions.

For

this sort of reason the Fi-Cord never really caught on and had

very little use. At the other end of the scale, for doing

high-quality recordings without the need for a carload of gear,

the Nagra (right) could be used, though as it was extremely

expensive an engineer was required to go along to operate it. It

was 14¼ by 9½ by 43/8

inches, and weighed almost 16lbs (so heavier even than the EMI

midget). It could record at 15 ips as well as 7½ and 3¾ ips on 7

inch reels, thus making it more suitable for music, and its very

high quality produced results well up to the standard of the

best studio machines. Obviously it was suitable only for special

occasions.

An

interesting, if not very useful, development, was the Nagra SN

(left), available from 1972, a sub-miniature machine built like

a Swiss watch. It was less than 6 inches long, and used 2½ inch

reels of 1/8 inch

double-play tape (the same as used in Compact Cassette

recorders) : there was no powered rewind. The machine would fit

in a pocket and was capable of very high quality, but it was

fiddly to use, and the tape could very easily be damaged; it

never really caught on for broadcasting (although it was popular

in America for security and covert surveillance work).

An

interesting, if not very useful, development, was the Nagra SN

(left), available from 1972, a sub-miniature machine built like

a Swiss watch. It was less than 6 inches long, and used 2½ inch

reels of 1/8 inch

double-play tape (the same as used in Compact Cassette

recorders) : there was no powered rewind. The machine would fit

in a pocket and was capable of very high quality, but it was

fiddly to use, and the tape could very easily be damaged; it

never really caught on for broadcasting (although it was popular

in America for security and covert surveillance work).

The ubiquitous Philips Compact Cassette (right),

introduced in 1963, was more promising. Initially designed for

dictation, it soon caught on for domestic use because of the

ease of operation: but it was only the addition of Dolby 'B'

noise reduction that made the quality anywhere near acceptable

for professional use. The 1/8

inch tape travelled at the very slow speed of 17/8

ips,

bringing problems of dirt pickup, alignment, tape noise and

flutter. The alignment of the tape to the head depended on the

enclosing cassette itself , and it was difficult to get a match

between two different machines.

The ubiquitous Philips Compact Cassette (right),

introduced in 1963, was more promising. Initially designed for

dictation, it soon caught on for domestic use because of the

ease of operation: but it was only the addition of Dolby 'B'

noise reduction that made the quality anywhere near acceptable

for professional use. The 1/8

inch tape travelled at the very slow speed of 17/8

ips,

bringing problems of dirt pickup, alignment, tape noise and

flutter. The alignment of the tape to the head depended on the

enclosing cassette itself , and it was difficult to get a match

between two different machines.

Some small and well-designed recorders were used for a time, particularly the Sony Walkman Pro (left), and were popular with producers as they were so easy to handle, but it was never an entirely suitable format for broadcasting (though full-sized machines were installed in studios to make reference recordings of transmissions, not for programme use but to be kept in case of queries).

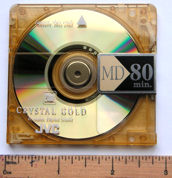

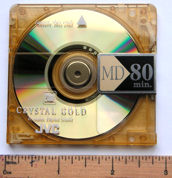

Sony

pitched their MiniDisc system, introduced in 1992, as a

replacement for the ageing Philips Cassette: it certainly had

everything going for it. The small magneto-optical disks (right)

were encased in a holder and easy to handle and load: the

digital recording quality was excellent, despite the use of

compression, and the disks could hold 75 minutes of high-quality

stereo making them comparable to CDs. They never really caught

on with the general public, though amateurs interested in

high-quality recording found them a useful replacement for

open-reel recorders. The recordings could even be edited, though

it was a fiddly process.

Sony

pitched their MiniDisc system, introduced in 1992, as a

replacement for the ageing Philips Cassette: it certainly had

everything going for it. The small magneto-optical disks (right)

were encased in a holder and easy to handle and load: the

digital recording quality was excellent, despite the use of

compression, and the disks could hold 75 minutes of high-quality

stereo making them comparable to CDs. They never really caught

on with the general public, though amateurs interested in

high-quality recording found them a useful replacement for

open-reel recorders. The recordings could even be edited, though

it was a fiddly process.

Small

machines were available, having a footprint not much bigger than

the disk itself; these were intended by Sony as replacements for

the cassette 'Walkman' which had revolutionized personal

listening (then came the iPod...): the top-level version of this

range, which could also record, was used for a time by the BBC

for portable recordings (left). The controls were fiddly, but

the machines reasonably robust, without any of the difficulties

experienced with the mini-Nagra, the Fi-Cord or cassettes.

Small

machines were available, having a footprint not much bigger than

the disk itself; these were intended by Sony as replacements for

the cassette 'Walkman' which had revolutionized personal

listening (then came the iPod...): the top-level version of this

range, which could also record, was used for a time by the BBC

for portable recordings (left). The controls were fiddly, but

the machines reasonably robust, without any of the difficulties

experienced with the mini-Nagra, the Fi-Cord or cassettes.

Another

system using digital recording was DAT - Digital Audio Tape: the

device mechanism was a minaturized version of the domestic video

recorder, complete with spinning drum and a complex automatic

lace-up: it used cassettes similar in appearance to standard

audio cassettes. The portable versions had some use, with larger

models in some studios used for transfers and reference

recordings, but they were often unreliable and prone to

dropouts. Both these types of machine saw some use until a

completely new approach to recording came in in the 1990s.

Another

system using digital recording was DAT - Digital Audio Tape: the

device mechanism was a minaturized version of the domestic video

recorder, complete with spinning drum and a complex automatic

lace-up: it used cassettes similar in appearance to standard

audio cassettes. The portable versions had some use, with larger

models in some studios used for transfers and reference

recordings, but they were often unreliable and prone to

dropouts. Both these types of machine saw some use until a

completely new approach to recording came in in the 1990s.

One disadvantage of all

the above-mentioned machines except the EMI Midget and the large

Nagra was that it was advisable - and in most cases necessary -

to take the time to copy the recording to normal open-reel tape

before editing. The advent of digital systems opened new

possibilities here, with a number of small digital recorders

becoming available. Most were intended for dictation or

note-taking, with mediocre quality: but the Mayah Flashman

(right), introduced in 2002, took a fully professional approach

to the idea. At 5 by 2¼ by 5¾ inches and weighing 715 grams

(less than 2 lbs) it also had no moving parts, making it

extremely robust.

One disadvantage of all

the above-mentioned machines except the EMI Midget and the large

Nagra was that it was advisable - and in most cases necessary -

to take the time to copy the recording to normal open-reel tape

before editing. The advent of digital systems opened new

possibilities here, with a number of small digital recorders

becoming available. Most were intended for dictation or

note-taking, with mediocre quality: but the Mayah Flashman

(right), introduced in 2002, took a fully professional approach

to the idea. At 5 by 2¼ by 5¾ inches and weighing 715 grams

(less than 2 lbs) it also had no moving parts, making it

extremely robust.

It had an XLR connector

for professional microphones, and recorded high-quality stereo

in a variety of digital formats to a Compact Flash

digital card (left): on return to base this card could be

plugged into a computer with audio facilities and the recording

transferred in a matter of seconds. The machine would record for

2½ hours and as it used standard AAA batteries it was an easy

matter to carry spares and change them.

It had an XLR connector

for professional microphones, and recorded high-quality stereo

in a variety of digital formats to a Compact Flash

digital card (left): on return to base this card could be

plugged into a computer with audio facilities and the recording

transferred in a matter of seconds. The machine would record for

2½ hours and as it used standard AAA batteries it was an easy

matter to carry spares and change them.

Though it was comparatively expensive at around £1000 (its Mark 2 replacement is around twice that) its quality, robustness and ease of use made it an obvious choice and it came into widespread use: similar devices from other manufacturers followed.

By the time it came into use digital recording and playout facilities were well on the way to replacing tape across the BBC and other broadcasts: a major change in the process of recording, which will be examined on the final page; the next page examines specialized use of recordings for signature tunes and stings,

1 INTRODUCTION

2 STEEL TAPE

3 OPTICAL FILM

4 DIRECTLY-CUT DISKS

5 MAGNETIC TAPE

6 PORTABLE RECORDING

7 CARTS AND DARTS

8 DIGITAL RECORDING AND PLAYOUT

While before the advent of magnetic tape it had been possible to do mobile recording - involving a car-full of equipment - the only portable recorder had been the BBC midget disk recorder, used by war correspondents - and that was no light weight. With tape it became possible to make much smaller and lighter devices, with the aim of allowing a single non-technical member of staff to go out and make a location recording such as an interview without involving a lot of complex equipment.

The

EMI Midget (left) was the first practicable device of this type

used by the BBC. Its size was 14 by 7 by 8 inches; initially

using valves (later versions were transistorized with consequent

savings on weight and battery usage) it recorded at 7½ips on

five-inch spools (holding 15 minutes): it had no erase head so

it was vital to use clean tape (more than one producer failed to

pay attention to this point and brought back an unusable

recording as a result).

The

EMI Midget (left) was the first practicable device of this type

used by the BBC. Its size was 14 by 7 by 8 inches; initially

using valves (later versions were transistorized with consequent

savings on weight and battery usage) it recorded at 7½ips on

five-inch spools (holding 15 minutes): it had no erase head so

it was vital to use clean tape (more than one producer failed to

pay attention to this point and brought back an unusable

recording as a result).Two sets of batteries were required, nine dry cells lasting about 6 hours for 'low tension' (valve heaters) and motors, and two 67.5 dry batteries for the 'high tension' supply, lasting about 15 hours. The quality was very good, and the tapes - which were recorded full-track, as with studio machines - could be rewound onto larger spools for immediate editing or use in a studio.

This machine considerably increased the freedom of producers to obtain inserts such as interviews or background effects for features; but weighing in at 14½ lbs (6½kg) it was still quite a heavy object to carry any distance; so there was always a need for smaller high-quality machines.

The

Uher portable (right) became available in the early 1960s and

rapidly replaced the EMI as the machine of choice; it soon

became standard issue. It recorded on 5 inch reels at speeds

of 7½, 3¾, 17/8 and 15/16

ips, though obviously only 7½ was ever used by the BBC. It

recorded half-track, like domestic machines, so it was advisable

to use clean tape, and if both tracks of the tape were used it

would have to be specially dubbed on return to the studio (this

was before stereo: all studio machines were full track). The

quality was excellent, though it was alarming how many

producer-made recordings came back somewhat distorted.

The

Uher portable (right) became available in the early 1960s and

rapidly replaced the EMI as the machine of choice; it soon

became standard issue. It recorded on 5 inch reels at speeds

of 7½, 3¾, 17/8 and 15/16

ips, though obviously only 7½ was ever used by the BBC. It

recorded half-track, like domestic machines, so it was advisable

to use clean tape, and if both tracks of the tape were used it

would have to be specially dubbed on return to the studio (this

was before stereo: all studio machines were full track). The

quality was excellent, though it was alarming how many

producer-made recordings came back somewhat distorted.A friend had his own Uher: on one occasion we were attempting to mimic the distorted sound of a producer-made recording for comic effect: we recorded so that the meter peaked well into the red overload area: and it sounded fine. So then we recorded with the meter never coming out of the red area: then it sounded like a producer-made recording.

The Uher was considerably lighter than the EMI at around 8lbs (3.6kg) but still heavy enough to make your shoulder ache if you carried it any distance; so there was always going to be a demand for really small machines. Unfortunately these tended to be domestic models with variable quality and poor reliability.

The

Fi-Cord (left) was marketed from 1959 for domestic use: it was

very small at 95/8 by 5 by

2¾ inches and weighed only 4½lbs (2kg). It used 3 inch spools

containing long play (1 thousandth of an inch thick) tape which

would run for eight minutes at 7½ips - the very thin tape needed

careful handling and had to be dubbed on return to base as it

couldn't be reliably edited or played in a studio. The quality

was capable of being very good, but the machine was touchy and

tricky to use. One producer brought me a tape which had been

laced with a small amount sticking out underneath the reel: this

had caused the machine to proceed in a series of jerks. He asked

if I could use the variable-speed unit to correct this...

The

Fi-Cord (left) was marketed from 1959 for domestic use: it was

very small at 95/8 by 5 by

2¾ inches and weighed only 4½lbs (2kg). It used 3 inch spools

containing long play (1 thousandth of an inch thick) tape which

would run for eight minutes at 7½ips - the very thin tape needed

careful handling and had to be dubbed on return to base as it

couldn't be reliably edited or played in a studio. The quality

was capable of being very good, but the machine was touchy and

tricky to use. One producer brought me a tape which had been

laced with a small amount sticking out underneath the reel: this

had caused the machine to proceed in a series of jerks. He asked

if I could use the variable-speed unit to correct this... For

this sort of reason the Fi-Cord never really caught on and had

very little use. At the other end of the scale, for doing

high-quality recordings without the need for a carload of gear,

the Nagra (right) could be used, though as it was extremely

expensive an engineer was required to go along to operate it. It

was 14¼ by 9½ by 43/8

inches, and weighed almost 16lbs (so heavier even than the EMI

midget). It could record at 15 ips as well as 7½ and 3¾ ips on 7

inch reels, thus making it more suitable for music, and its very

high quality produced results well up to the standard of the

best studio machines. Obviously it was suitable only for special

occasions.

For

this sort of reason the Fi-Cord never really caught on and had

very little use. At the other end of the scale, for doing

high-quality recordings without the need for a carload of gear,

the Nagra (right) could be used, though as it was extremely

expensive an engineer was required to go along to operate it. It

was 14¼ by 9½ by 43/8

inches, and weighed almost 16lbs (so heavier even than the EMI

midget). It could record at 15 ips as well as 7½ and 3¾ ips on 7

inch reels, thus making it more suitable for music, and its very

high quality produced results well up to the standard of the

best studio machines. Obviously it was suitable only for special

occasions. An

interesting, if not very useful, development, was the Nagra SN

(left), available from 1972, a sub-miniature machine built like

a Swiss watch. It was less than 6 inches long, and used 2½ inch

reels of 1/8 inch

double-play tape (the same as used in Compact Cassette

recorders) : there was no powered rewind. The machine would fit

in a pocket and was capable of very high quality, but it was

fiddly to use, and the tape could very easily be damaged; it

never really caught on for broadcasting (although it was popular

in America for security and covert surveillance work).

An

interesting, if not very useful, development, was the Nagra SN

(left), available from 1972, a sub-miniature machine built like

a Swiss watch. It was less than 6 inches long, and used 2½ inch

reels of 1/8 inch

double-play tape (the same as used in Compact Cassette

recorders) : there was no powered rewind. The machine would fit

in a pocket and was capable of very high quality, but it was

fiddly to use, and the tape could very easily be damaged; it

never really caught on for broadcasting (although it was popular

in America for security and covert surveillance work). The ubiquitous Philips Compact Cassette (right),

introduced in 1963, was more promising. Initially designed for

dictation, it soon caught on for domestic use because of the

ease of operation: but it was only the addition of Dolby 'B'

noise reduction that made the quality anywhere near acceptable

for professional use. The 1/8

inch tape travelled at the very slow speed of 17/8

ips,

bringing problems of dirt pickup, alignment, tape noise and

flutter. The alignment of the tape to the head depended on the

enclosing cassette itself , and it was difficult to get a match

between two different machines.

The ubiquitous Philips Compact Cassette (right),

introduced in 1963, was more promising. Initially designed for

dictation, it soon caught on for domestic use because of the

ease of operation: but it was only the addition of Dolby 'B'

noise reduction that made the quality anywhere near acceptable

for professional use. The 1/8

inch tape travelled at the very slow speed of 17/8

ips,

bringing problems of dirt pickup, alignment, tape noise and

flutter. The alignment of the tape to the head depended on the

enclosing cassette itself , and it was difficult to get a match

between two different machines.

Some small and well-designed recorders were used for a time, particularly the Sony Walkman Pro (left), and were popular with producers as they were so easy to handle, but it was never an entirely suitable format for broadcasting (though full-sized machines were installed in studios to make reference recordings of transmissions, not for programme use but to be kept in case of queries).

Sony

pitched their MiniDisc system, introduced in 1992, as a

replacement for the ageing Philips Cassette: it certainly had

everything going for it. The small magneto-optical disks (right)

were encased in a holder and easy to handle and load: the

digital recording quality was excellent, despite the use of

compression, and the disks could hold 75 minutes of high-quality

stereo making them comparable to CDs. They never really caught

on with the general public, though amateurs interested in

high-quality recording found them a useful replacement for

open-reel recorders. The recordings could even be edited, though

it was a fiddly process.

Sony

pitched their MiniDisc system, introduced in 1992, as a

replacement for the ageing Philips Cassette: it certainly had

everything going for it. The small magneto-optical disks (right)

were encased in a holder and easy to handle and load: the

digital recording quality was excellent, despite the use of

compression, and the disks could hold 75 minutes of high-quality

stereo making them comparable to CDs. They never really caught

on with the general public, though amateurs interested in

high-quality recording found them a useful replacement for

open-reel recorders. The recordings could even be edited, though

it was a fiddly process. Small

machines were available, having a footprint not much bigger than

the disk itself; these were intended by Sony as replacements for

the cassette 'Walkman' which had revolutionized personal

listening (then came the iPod...): the top-level version of this

range, which could also record, was used for a time by the BBC

for portable recordings (left). The controls were fiddly, but

the machines reasonably robust, without any of the difficulties

experienced with the mini-Nagra, the Fi-Cord or cassettes.

Small

machines were available, having a footprint not much bigger than

the disk itself; these were intended by Sony as replacements for

the cassette 'Walkman' which had revolutionized personal

listening (then came the iPod...): the top-level version of this

range, which could also record, was used for a time by the BBC

for portable recordings (left). The controls were fiddly, but

the machines reasonably robust, without any of the difficulties

experienced with the mini-Nagra, the Fi-Cord or cassettes.  Another

system using digital recording was DAT - Digital Audio Tape: the

device mechanism was a minaturized version of the domestic video

recorder, complete with spinning drum and a complex automatic

lace-up: it used cassettes similar in appearance to standard

audio cassettes. The portable versions had some use, with larger

models in some studios used for transfers and reference

recordings, but they were often unreliable and prone to

dropouts. Both these types of machine saw some use until a

completely new approach to recording came in in the 1990s.

Another

system using digital recording was DAT - Digital Audio Tape: the

device mechanism was a minaturized version of the domestic video

recorder, complete with spinning drum and a complex automatic

lace-up: it used cassettes similar in appearance to standard

audio cassettes. The portable versions had some use, with larger

models in some studios used for transfers and reference

recordings, but they were often unreliable and prone to

dropouts. Both these types of machine saw some use until a

completely new approach to recording came in in the 1990s. One disadvantage of all

the above-mentioned machines except the EMI Midget and the large

Nagra was that it was advisable - and in most cases necessary -

to take the time to copy the recording to normal open-reel tape

before editing. The advent of digital systems opened new

possibilities here, with a number of small digital recorders

becoming available. Most were intended for dictation or

note-taking, with mediocre quality: but the Mayah Flashman

(right), introduced in 2002, took a fully professional approach

to the idea. At 5 by 2¼ by 5¾ inches and weighing 715 grams

(less than 2 lbs) it also had no moving parts, making it

extremely robust.

One disadvantage of all

the above-mentioned machines except the EMI Midget and the large

Nagra was that it was advisable - and in most cases necessary -

to take the time to copy the recording to normal open-reel tape

before editing. The advent of digital systems opened new

possibilities here, with a number of small digital recorders

becoming available. Most were intended for dictation or

note-taking, with mediocre quality: but the Mayah Flashman

(right), introduced in 2002, took a fully professional approach

to the idea. At 5 by 2¼ by 5¾ inches and weighing 715 grams

(less than 2 lbs) it also had no moving parts, making it

extremely robust. It had an XLR connector

for professional microphones, and recorded high-quality stereo

in a variety of digital formats to a Compact Flash

digital card (left): on return to base this card could be

plugged into a computer with audio facilities and the recording

transferred in a matter of seconds. The machine would record for

2½ hours and as it used standard AAA batteries it was an easy

matter to carry spares and change them.

It had an XLR connector

for professional microphones, and recorded high-quality stereo

in a variety of digital formats to a Compact Flash

digital card (left): on return to base this card could be

plugged into a computer with audio facilities and the recording

transferred in a matter of seconds. The machine would record for

2½ hours and as it used standard AAA batteries it was an easy

matter to carry spares and change them.Though it was comparatively expensive at around £1000 (its Mark 2 replacement is around twice that) its quality, robustness and ease of use made it an obvious choice and it came into widespread use: similar devices from other manufacturers followed.

By the time it came into use digital recording and playout facilities were well on the way to replacing tape across the BBC and other broadcasts: a major change in the process of recording, which will be examined on the final page; the next page examines specialized use of recordings for signature tunes and stings,