CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION

2 STEEL TAPE

3 OPTICAL FILM

4 DIRECTLY-CUT DISKS

5 MAGNETIC TAPE

6 PORTABLE RECORDING

7 CARTS AND DARTS

8 DIGITAL RECORDING AND PLAYOUT

Steel tape had proved useful, but was awkward and not of the best sound quality. During the war, monitors became aware that the Germans were evidently able to make high-quality recordings, since Hitler's speeches were being broadcast at all hours in what sounded like 'live' quality: during the invasion a number of radio stations were captured, equipped with recorders using ¼-inch tape on a cellulose acetate base, coated with a fine layer of iron oxide (Fe2O3) - paper had been in use as a base just before the war but broke so easily that it was impracticable.

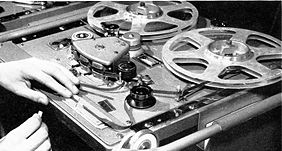

The

BBC acquired some

Magnetophone machines (left) in 1946 on an experimental basis,

and

these were used in the early stages of the new Third Programme

to

record and playback performances of operas from Germany (live

relays

being problematic because of the unreliability of the landlines

in the

immediate post-war period). The tapes ran at 30

inches/second (ips), and the flexible base provided much better

contact

with

the head: the main reason for the improvement in the sound was

the

addition of a high-frequency current at 100kHz to the audio

signal,

which avoided the inherent distortion in the magnetization

process.

The

BBC acquired some

Magnetophone machines (left) in 1946 on an experimental basis,

and

these were used in the early stages of the new Third Programme

to

record and playback performances of operas from Germany (live

relays

being problematic because of the unreliability of the landlines

in the

immediate post-war period). The tapes ran at 30

inches/second (ips), and the flexible base provided much better

contact

with

the head: the main reason for the improvement in the sound was

the

addition of a high-frequency current at 100kHz to the audio

signal,

which avoided the inherent distortion in the magnetization

process.

These machines were used until 1952, though most of the work continued to be done using the established media; but from 1948 a new British model became available from EMI: the BTR1. Though in many ways clumsy, its quality was good, and as it wasn't possible to obtain any more Magnetophones it was an obvious choice. There was some difficulty with the tape: early EMI tape was very prone to print-through (where the magnetic image on one layer causes the next layer on the spool to pick up a faint version, causing pre- and post-echoes, often through several layers) - I've been told that the BBC told EMI to sort this out or they would stop using tape. The effect remained in later years, but much diminished and normally not a serious problem.

We

still had one of

the BTR1s in the 1960s and I've had the doubtful pleasure of

using it.

It

was rather a nightmare: the operating buttons were connected to

the

mechanics by Bowden cable and were stiff, so you rapidly got a

sore

thumb. Worse, the head-block, because of its size, had to be

outside

the tape path with the heads facing away from you (and the tape

wound

oxide-out) so that marking the tape with a chinagraph pencil

involved

leaning over - I'm six feet tall and I found it awkward: shorter

colleagues found it nearly impossible. In the early days, at 30

ips,

people probably just grabbed the tape and cut it - at that speed

you

could afford to miss by a couple of inches as long as you

weren't doing

music editing. (Early editing was done by holding the tape in

mid-air

and using scissors - I once asked a colleague who had done this

how he

managed to get the angle consistent: he said, 'Oh, we didn't

bother'.

Of course at 30 ips it wouldn't matter much, but one of my more

eccentric colleagues insisted on using scissors at 7½ ips, and

his

joints were a menace.)

We

still had one of

the BTR1s in the 1960s and I've had the doubtful pleasure of

using it.

It

was rather a nightmare: the operating buttons were connected to

the

mechanics by Bowden cable and were stiff, so you rapidly got a

sore

thumb. Worse, the head-block, because of its size, had to be

outside

the tape path with the heads facing away from you (and the tape

wound

oxide-out) so that marking the tape with a chinagraph pencil

involved

leaning over - I'm six feet tall and I found it awkward: shorter

colleagues found it nearly impossible. In the early days, at 30

ips,

people probably just grabbed the tape and cut it - at that speed

you

could afford to miss by a couple of inches as long as you

weren't doing

music editing. (Early editing was done by holding the tape in

mid-air

and using scissors - I once asked a colleague who had done this

how he

managed to get the angle consistent: he said, 'Oh, we didn't

bother'.

Of course at 30 ips it wouldn't matter much, but one of my more

eccentric colleagues insisted on using scissors at 7½ ips, and

his

joints were a menace.)

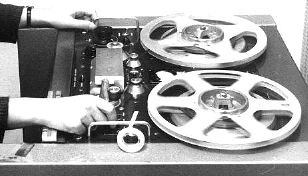

In the

early 1950s the EMI BTR 2 became

available

(left); a much improved machine and generally liked. It became

the

standard in recording channels (rooms) for many years, and was

in use

until the end of the 1960s. The machines were responsive, could

run up

to speed quite quickly, had light-touch operating buttons,

forward-facing heads, and were quick and easy to do the finest

editing

on.

In the

early 1950s the EMI BTR 2 became

available

(left); a much improved machine and generally liked. It became

the

standard in recording channels (rooms) for many years, and was

in use

until the end of the 1960s. The machines were responsive, could

run up

to speed quite quickly, had light-touch operating buttons,

forward-facing heads, and were quick and easy to do the finest

editing

on.

The tape speed was eventually standardized at 15 ips for almost all work at Broadcasting House, and at 15 ips for music and 7½ ips for speech at Bush House. The acetate base was replaced by PVC which broke less easily (though when it did it stretched, whereas acetate snapped cleanly and was easy to repair: stretched PVC was a disaster). The standard 10½ inch reels ran for half an hour at 15 ips with standard thickness tape (1.5 thousandths of an inch - 'long play' tape at 1 thousandth was available for domestic use but stretched too easily for broadcast use). In the end Bush House abandoned 15 ips for pretty well everything: and in 1971 embarked on an ill-advised experiment to use 3¾ ips to cut down on the considerable cost of tape. We all told them it wouldn't work: and it didn't - after a few weeks it was abandoned as the quality couldn't be maintained and joints tended to lift off the head in passing through.

The

BTR 1 and 2 revolutionized broadcasting. The

quality was

indistiguishable from live on transmission, and the finest

editing

could

be done quickly and easily by practised engineers; instead of

film

cement or soldering irons the simple application of sticky tape

to the

edited tape held in a block made the process much simpler

(right).

Variety programmes

could be recorded on Sunday, allowing the performers to appear

in

Music-Halls during the week, and the producer could edit the

programme

to tighten it up, get it to the correct length, and remove

dubious

jokes which had been slipped in (always a problem in the 1930s).

The

machines' speed reliability over 30 minutes was not perfect, so

the

tradition arose of programmes running 29 minutes and 30 seconds,

with a

1 minute music playout, so that an error of ±30 seconds could be

accomodated (this was before programme junctions were cluttered

up with

two minutes of trails).

The

BTR 1 and 2 revolutionized broadcasting. The

quality was

indistiguishable from live on transmission, and the finest

editing

could

be done quickly and easily by practised engineers; instead of

film

cement or soldering irons the simple application of sticky tape

to the

edited tape held in a block made the process much simpler

(right).

Variety programmes

could be recorded on Sunday, allowing the performers to appear

in

Music-Halls during the week, and the producer could edit the

programme

to tighten it up, get it to the correct length, and remove

dubious

jokes which had been slipped in (always a problem in the 1930s).

The

machines' speed reliability over 30 minutes was not perfect, so

the

tradition arose of programmes running 29 minutes and 30 seconds,

with a

1 minute music playout, so that an error of ±30 seconds could be

accomodated (this was before programme junctions were cluttered

up with

two minutes of trails).

It also became normal to 'de-umm' pre-recorded interviews - particularly in the World Service where the interviewee was often not completely fluent in English: the most edits I ever had (I actually counted the number of pieces of sticky tape as they went past on-air) was 75 in a three-minute interview, though this was abnormally high.

Up until about 1965 there were no tape machines in Bush House or Broadcasting House studios: Studio Managers handled the mixing panel and played disks, but never touched tape - all recording, editing and playback was done in channels (except that occasionally at Broadcasting House a smaller tape machine was in use in the studio, but with an engineer in attendance. Producers weren't allowed to handle tape either - the engineers sent recordings to a central library and all handling of tapes was carried out by Engineering Department).

With the increased reliability of tape the decision was taken to equip studios with tape machines - initially for playback only, though eventually local recording was introduced and Studio Managers had to become fully conversant with the machines (there was some resistance to this as SMs were usually from a non-technical background). BTR2s were too big for studio use, and various other machines became available.

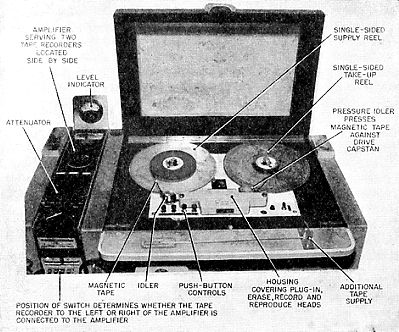

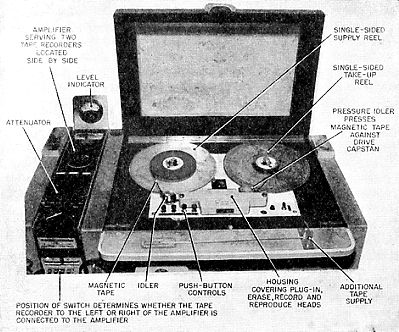

Broadcasting

House used the EMI TR90 (left) and a Philips machine which was

lightweight but very easy and quick to use: Bush House used the

Leevers-Rich, initially in the widely-disliked Mark 2 version

(right)

but later with the push-button operated Mark 4 - which was an

improvement, though the complicated tape lace-up path was still

not

popular.

Broadcasting

House used the EMI TR90 (left) and a Philips machine which was

lightweight but very easy and quick to use: Bush House used the

Leevers-Rich, initially in the widely-disliked Mark 2 version

(right)

but later with the push-button operated Mark 4 - which was an

improvement, though the complicated tape lace-up path was still

not

popular.

The

Studer range of machines had become pretty well the studio

recording

industry standard by the 1970s, and gradually these replaced the

aging

BTR2s (which were now giving flutter and general reliability

problems,

with no spares available) in recording rooms and studios: the

photo on

the right is of the first model to arrive at Bush House, and

later

similar but refined versions were eventually installed in the

larger

studios. As delivered the machines had a motorized pair of

scissors

which popped out of a slot before the final roller, and was

supposed to

be used to edit the tape (you found the place then moved the

tape on by

an amount shown on the right-hand roller): it's a daft idea, and

after

someone had managed to snip a tape while it was being played up

a line

to Scotland (who thought it hilarious) the scissors were

disabled to

prevent

further accidents.

The

Studer range of machines had become pretty well the studio

recording

industry standard by the 1970s, and gradually these replaced the

aging

BTR2s (which were now giving flutter and general reliability

problems,

with no spares available) in recording rooms and studios: the

photo on

the right is of the first model to arrive at Bush House, and

later

similar but refined versions were eventually installed in the

larger

studios. As delivered the machines had a motorized pair of

scissors

which popped out of a slot before the final roller, and was

supposed to

be used to edit the tape (you found the place then moved the

tape on by

an amount shown on the right-hand roller): it's a daft idea, and

after

someone had managed to snip a tape while it was being played up

a line

to Scotland (who thought it hilarious) the scissors were

disabled to

prevent

further accidents.

Gradually pre-recorded rather than live programmes - or inserts - became the norm. Recording in sections and subsequent editing and mixing enabled broadcast plays to be be assembled with less rehearsal, but something of the 'edge' of classic live plays such as Under Milk Wood and The Dark Tower was lost in the process. Of course there were new hazards: accidental erasure (fortunately not common, but it could happen: someone once placed a 4038 microphone - which contains a very powerful magnet - on top of a reel of tape, with obvious results), tapes dropped down lift-shafts or taken home in error (more than one Studio Manager has been woken in the night and told to bring a recording needed for overnight transmission back now), or stretched by mishandling (as an engineer I once saved an SM's skin by reconstructing the damaged word 'United' from syllables copied from elsewhere in the recording, and I don't claim any uniqueness about that).

So the advent of magnetic tape recording had more effect on radio than anything since its inception (and a similar process was taking place in television with the invention of video recording); and one of its major contributions was in providing the ability to make location recordings without lugging a car-load of touchy disk-cutting equipment about: portable recording will be examined on the next page.

1 INTRODUCTION

2 STEEL TAPE

3 OPTICAL FILM

4 DIRECTLY-CUT DISKS

5 MAGNETIC TAPE

6 PORTABLE RECORDING

7 CARTS AND DARTS

8 DIGITAL RECORDING AND PLAYOUT

Steel tape had proved useful, but was awkward and not of the best sound quality. During the war, monitors became aware that the Germans were evidently able to make high-quality recordings, since Hitler's speeches were being broadcast at all hours in what sounded like 'live' quality: during the invasion a number of radio stations were captured, equipped with recorders using ¼-inch tape on a cellulose acetate base, coated with a fine layer of iron oxide (Fe2O3) - paper had been in use as a base just before the war but broke so easily that it was impracticable.

The

BBC acquired some

Magnetophone machines (left) in 1946 on an experimental basis,

and

these were used in the early stages of the new Third Programme

to

record and playback performances of operas from Germany (live

relays

being problematic because of the unreliability of the landlines

in the

immediate post-war period). The tapes ran at 30

inches/second (ips), and the flexible base provided much better

contact

with

the head: the main reason for the improvement in the sound was

the

addition of a high-frequency current at 100kHz to the audio

signal,

which avoided the inherent distortion in the magnetization

process.

The

BBC acquired some

Magnetophone machines (left) in 1946 on an experimental basis,

and

these were used in the early stages of the new Third Programme

to

record and playback performances of operas from Germany (live

relays

being problematic because of the unreliability of the landlines

in the

immediate post-war period). The tapes ran at 30

inches/second (ips), and the flexible base provided much better

contact

with

the head: the main reason for the improvement in the sound was

the

addition of a high-frequency current at 100kHz to the audio

signal,

which avoided the inherent distortion in the magnetization

process.These machines were used until 1952, though most of the work continued to be done using the established media; but from 1948 a new British model became available from EMI: the BTR1. Though in many ways clumsy, its quality was good, and as it wasn't possible to obtain any more Magnetophones it was an obvious choice. There was some difficulty with the tape: early EMI tape was very prone to print-through (where the magnetic image on one layer causes the next layer on the spool to pick up a faint version, causing pre- and post-echoes, often through several layers) - I've been told that the BBC told EMI to sort this out or they would stop using tape. The effect remained in later years, but much diminished and normally not a serious problem.

We

still had one of

the BTR1s in the 1960s and I've had the doubtful pleasure of

using it.

It

was rather a nightmare: the operating buttons were connected to

the

mechanics by Bowden cable and were stiff, so you rapidly got a

sore

thumb. Worse, the head-block, because of its size, had to be

outside

the tape path with the heads facing away from you (and the tape

wound

oxide-out) so that marking the tape with a chinagraph pencil

involved

leaning over - I'm six feet tall and I found it awkward: shorter

colleagues found it nearly impossible. In the early days, at 30

ips,

people probably just grabbed the tape and cut it - at that speed

you

could afford to miss by a couple of inches as long as you

weren't doing

music editing. (Early editing was done by holding the tape in

mid-air

and using scissors - I once asked a colleague who had done this

how he

managed to get the angle consistent: he said, 'Oh, we didn't

bother'.

Of course at 30 ips it wouldn't matter much, but one of my more

eccentric colleagues insisted on using scissors at 7½ ips, and

his

joints were a menace.)

We

still had one of

the BTR1s in the 1960s and I've had the doubtful pleasure of

using it.

It

was rather a nightmare: the operating buttons were connected to

the

mechanics by Bowden cable and were stiff, so you rapidly got a

sore

thumb. Worse, the head-block, because of its size, had to be

outside

the tape path with the heads facing away from you (and the tape

wound

oxide-out) so that marking the tape with a chinagraph pencil

involved

leaning over - I'm six feet tall and I found it awkward: shorter

colleagues found it nearly impossible. In the early days, at 30

ips,

people probably just grabbed the tape and cut it - at that speed

you

could afford to miss by a couple of inches as long as you

weren't doing

music editing. (Early editing was done by holding the tape in

mid-air

and using scissors - I once asked a colleague who had done this

how he

managed to get the angle consistent: he said, 'Oh, we didn't

bother'.

Of course at 30 ips it wouldn't matter much, but one of my more

eccentric colleagues insisted on using scissors at 7½ ips, and

his

joints were a menace.) In the

early 1950s the EMI BTR 2 became

available

(left); a much improved machine and generally liked. It became

the

standard in recording channels (rooms) for many years, and was

in use

until the end of the 1960s. The machines were responsive, could

run up

to speed quite quickly, had light-touch operating buttons,

forward-facing heads, and were quick and easy to do the finest

editing

on.

In the

early 1950s the EMI BTR 2 became

available

(left); a much improved machine and generally liked. It became

the

standard in recording channels (rooms) for many years, and was

in use

until the end of the 1960s. The machines were responsive, could

run up

to speed quite quickly, had light-touch operating buttons,

forward-facing heads, and were quick and easy to do the finest

editing

on.The tape speed was eventually standardized at 15 ips for almost all work at Broadcasting House, and at 15 ips for music and 7½ ips for speech at Bush House. The acetate base was replaced by PVC which broke less easily (though when it did it stretched, whereas acetate snapped cleanly and was easy to repair: stretched PVC was a disaster). The standard 10½ inch reels ran for half an hour at 15 ips with standard thickness tape (1.5 thousandths of an inch - 'long play' tape at 1 thousandth was available for domestic use but stretched too easily for broadcast use). In the end Bush House abandoned 15 ips for pretty well everything: and in 1971 embarked on an ill-advised experiment to use 3¾ ips to cut down on the considerable cost of tape. We all told them it wouldn't work: and it didn't - after a few weeks it was abandoned as the quality couldn't be maintained and joints tended to lift off the head in passing through.

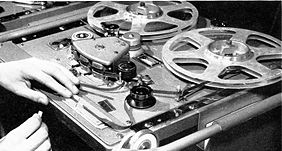

The

BTR 1 and 2 revolutionized broadcasting. The

quality was

indistiguishable from live on transmission, and the finest

editing

could

be done quickly and easily by practised engineers; instead of

film

cement or soldering irons the simple application of sticky tape

to the

edited tape held in a block made the process much simpler

(right).

Variety programmes

could be recorded on Sunday, allowing the performers to appear

in

Music-Halls during the week, and the producer could edit the

programme

to tighten it up, get it to the correct length, and remove

dubious

jokes which had been slipped in (always a problem in the 1930s).

The

machines' speed reliability over 30 minutes was not perfect, so

the

tradition arose of programmes running 29 minutes and 30 seconds,

with a

1 minute music playout, so that an error of ±30 seconds could be

accomodated (this was before programme junctions were cluttered

up with

two minutes of trails).

The

BTR 1 and 2 revolutionized broadcasting. The

quality was

indistiguishable from live on transmission, and the finest

editing

could

be done quickly and easily by practised engineers; instead of

film

cement or soldering irons the simple application of sticky tape

to the

edited tape held in a block made the process much simpler

(right).

Variety programmes

could be recorded on Sunday, allowing the performers to appear

in

Music-Halls during the week, and the producer could edit the

programme

to tighten it up, get it to the correct length, and remove

dubious

jokes which had been slipped in (always a problem in the 1930s).

The

machines' speed reliability over 30 minutes was not perfect, so

the

tradition arose of programmes running 29 minutes and 30 seconds,

with a

1 minute music playout, so that an error of ±30 seconds could be

accomodated (this was before programme junctions were cluttered

up with

two minutes of trails).It also became normal to 'de-umm' pre-recorded interviews - particularly in the World Service where the interviewee was often not completely fluent in English: the most edits I ever had (I actually counted the number of pieces of sticky tape as they went past on-air) was 75 in a three-minute interview, though this was abnormally high.

Up until about 1965 there were no tape machines in Bush House or Broadcasting House studios: Studio Managers handled the mixing panel and played disks, but never touched tape - all recording, editing and playback was done in channels (except that occasionally at Broadcasting House a smaller tape machine was in use in the studio, but with an engineer in attendance. Producers weren't allowed to handle tape either - the engineers sent recordings to a central library and all handling of tapes was carried out by Engineering Department).

With the increased reliability of tape the decision was taken to equip studios with tape machines - initially for playback only, though eventually local recording was introduced and Studio Managers had to become fully conversant with the machines (there was some resistance to this as SMs were usually from a non-technical background). BTR2s were too big for studio use, and various other machines became available.

Broadcasting

House used the EMI TR90 (left) and a Philips machine which was

lightweight but very easy and quick to use: Bush House used the

Leevers-Rich, initially in the widely-disliked Mark 2 version

(right)

but later with the push-button operated Mark 4 - which was an

improvement, though the complicated tape lace-up path was still

not

popular.

Broadcasting

House used the EMI TR90 (left) and a Philips machine which was

lightweight but very easy and quick to use: Bush House used the

Leevers-Rich, initially in the widely-disliked Mark 2 version

(right)

but later with the push-button operated Mark 4 - which was an

improvement, though the complicated tape lace-up path was still

not

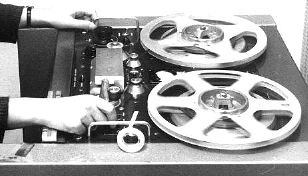

popular. The

Studer range of machines had become pretty well the studio

recording

industry standard by the 1970s, and gradually these replaced the

aging

BTR2s (which were now giving flutter and general reliability

problems,

with no spares available) in recording rooms and studios: the

photo on

the right is of the first model to arrive at Bush House, and

later

similar but refined versions were eventually installed in the

larger

studios. As delivered the machines had a motorized pair of

scissors

which popped out of a slot before the final roller, and was

supposed to

be used to edit the tape (you found the place then moved the

tape on by

an amount shown on the right-hand roller): it's a daft idea, and

after

someone had managed to snip a tape while it was being played up

a line

to Scotland (who thought it hilarious) the scissors were

disabled to

prevent

further accidents.

The

Studer range of machines had become pretty well the studio

recording

industry standard by the 1970s, and gradually these replaced the

aging

BTR2s (which were now giving flutter and general reliability

problems,

with no spares available) in recording rooms and studios: the

photo on

the right is of the first model to arrive at Bush House, and

later

similar but refined versions were eventually installed in the

larger

studios. As delivered the machines had a motorized pair of

scissors

which popped out of a slot before the final roller, and was

supposed to

be used to edit the tape (you found the place then moved the

tape on by

an amount shown on the right-hand roller): it's a daft idea, and

after

someone had managed to snip a tape while it was being played up

a line

to Scotland (who thought it hilarious) the scissors were

disabled to

prevent

further accidents.Gradually pre-recorded rather than live programmes - or inserts - became the norm. Recording in sections and subsequent editing and mixing enabled broadcast plays to be be assembled with less rehearsal, but something of the 'edge' of classic live plays such as Under Milk Wood and The Dark Tower was lost in the process. Of course there were new hazards: accidental erasure (fortunately not common, but it could happen: someone once placed a 4038 microphone - which contains a very powerful magnet - on top of a reel of tape, with obvious results), tapes dropped down lift-shafts or taken home in error (more than one Studio Manager has been woken in the night and told to bring a recording needed for overnight transmission back now), or stretched by mishandling (as an engineer I once saved an SM's skin by reconstructing the damaged word 'United' from syllables copied from elsewhere in the recording, and I don't claim any uniqueness about that).

So the advent of magnetic tape recording had more effect on radio than anything since its inception (and a similar process was taking place in television with the invention of video recording); and one of its major contributions was in providing the ability to make location recordings without lugging a car-load of touchy disk-cutting equipment about: portable recording will be examined on the next page.