CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION

2 STEEL TAPE

3 OPTICAL FILM

4 DIRECTLY-CUT DISKS

5 MAGNETIC TAPE

6 PORTABLE RECORDING

7 CARTS AND DARTS

8 DIGITAL RECORDING AND PLAYOUT

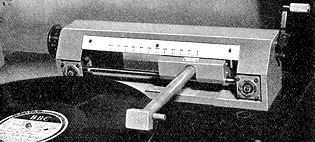

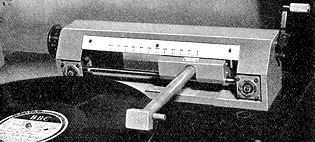

The normal method of producing gramophone records was not suitable for the BBC because of the long delay before a playable copy could be made (and the cost). From the early 1930s a British inventor, Cecil Watts, was working on a form of disk which could be played back immediately: by 1934 he had a workable method involving a laquer coating on an aluminium disk and was running a firm called M.S.S. to manufacture them and the disk-cutters. The blanks could be cut in the same way as wax blanks had been, but could be played back immediately - though obviously the laquer was much softer than a normal gramophone record and repeated playings would wear it much more quickly. The BBC started experimenting with this: at first there were difficulties because of the quality of the lacquer but eventually things settled down and the system came into regular use. The photo shows a M.S.S. disk-cutting channel, the first type the BBC used.

On playback the engineer would start the second disk, listening on headphones, pull it into sync by spinning or holding back the turntable (which wasn't heavy) and changing over once the two matched: though requiring some skill it isn't as impossible a task as it sounds (I've done it myself).

Disk recording was particularly suited to making location recordings, and the model C disk-cutter (right) was developed; this could be carried in an ordinary car and used to record interviews and so on. (This would be termed a 'transportable' machine, i.e. not actually bolted down: truly 'portable' machines would mean capable of being carried by one person).

With the onset

of the war came

a requirement for reporters in battle

zones to be able to record reports. and so the BBC midget recorder was

developed. This was truly portable, though still very heavy, and used a

clockwork spring - as used in ordinary wind-up gramophones - to drive

the turntable, thus removing a lot of strain from the battery (which

still of course had to power a valve amplifier). The photo shows

Frank Gillard using one in action.

With the onset

of the war came

a requirement for reporters in battle

zones to be able to record reports. and so the BBC midget recorder was

developed. This was truly portable, though still very heavy, and used a

clockwork spring - as used in ordinary wind-up gramophones - to drive

the turntable, thus removing a lot of strain from the battery (which

still of course had to power a valve amplifier). The photo shows

Frank Gillard using one in action.

The onset of the war was also a driving force in the development of the disk recording. In 1941 a number of American Presto machines (below) were provided by the USA under lease-lend (some of these were intercepted and landed up at the bottom of the Atlantic). Many of these were for the Overseas Service at Bush House and were still in use over twenty years later: I cut a large number of disks on these as a young Engineer. The quality was surprisingly good - in fact better than 15 inches-per-second tape on the first play, though they did sound noisier once the producer had taken them to his office and played them a few times.

The

recording channels posed a safety risk: though for some reason normally

referred to as 'acetates' the laquer was in fact cellulose nitrate -

the same as non-safety cinema film. When you cut a disk the off-cut

comes off as a ribbon, called swarf. Although the cellulose nitrate is

safe enough when it's on the base, because this swarf is mixed with air

it is extremely inflammable. When I was on the training course at

Evesham the lecturer took a handful of the stuff outside onto the

concrete and dropped a match on it (I suspect this was to discourage us

from trying it). It went up immediately in six feet of flame, and I

could feel the heat on my face ten feet away - it's that dangerous.

The

recording channels posed a safety risk: though for some reason normally

referred to as 'acetates' the laquer was in fact cellulose nitrate -

the same as non-safety cinema film. When you cut a disk the off-cut

comes off as a ribbon, called swarf. Although the cellulose nitrate is

safe enough when it's on the base, because this swarf is mixed with air

it is extremely inflammable. When I was on the training course at

Evesham the lecturer took a handful of the stuff outside onto the

concrete and dropped a match on it (I suspect this was to discourage us

from trying it). It went up immediately in six feet of flame, and I

could feel the heat on my face ten feet away - it's that dangerous.

There is a legend that, at the BBC Studios in Oxford Street (which closed in 1957) a producer (later a well-known politician) knocked his pipe out in a bin marked 'fire' (thinking it contained sand) and the swarf in it set fire to the recording channel. At Bush House another producer dropped a match (which had gone out but was still warm) in a bin - this time the engineer had the presence of mind to put his foot on the bin, so there was no fire, but the fumes got into the ventilation system and caused the evacuation of the entire floor.

One of the cleaners saw some of this soft black stuff and took it home and stuffed a cushion with it... very fortunately someone found out about it and she was discouraged. She might as well have taken an incendiary bomb home - if someone had ignited it, it would have burned her house down.

The

Prestos served us well, and were still working reliably when they were

phased out in the mid-1960s; we also had several BBC Type D

disk-cutting channels, and though these were no better in the already

very good quality

of the finished result, they were much easier to handle, with a better

vacuum-clearance of swarf than the Prestos, push-button scrolling

rather than a handle to turn, and much easier line-up. (In both cases

not only did test cuts with a fixed-frequency tone have to be made to

get the level right, but the grooves had to be examined with a

microscope as you cut the test so that you could adjust the depth of

cut).

The

Prestos served us well, and were still working reliably when they were

phased out in the mid-1960s; we also had several BBC Type D

disk-cutting channels, and though these were no better in the already

very good quality

of the finished result, they were much easier to handle, with a better

vacuum-clearance of swarf than the Prestos, push-button scrolling

rather than a handle to turn, and much easier line-up. (In both cases

not only did test cuts with a fixed-frequency tone have to be made to

get the level right, but the grooves had to be examined with a

microscope as you cut the test so that you could adjust the depth of

cut).

Almost all these recordings were made at 78rpm. There had been some use of 60rpm in the early days but this had been abandoned. Indeed the 1950 BBC Recording Training Manual devotes two pages to a mathematical proof that recording at 54rpm increases the maximum time without degrading the quality, before concluding that as commercial recordings are made at 78rpm it's better to stick at that. Recordings were also made at 331/3rpm on 17 inch disks (using the same sized grooves as 78rpm): as one side would hold ten minutes this system was widely used at Broadcasting House for recording complete programmes.

Another

reason for the continued use of disks

was

that up until the

late 1960s there were no tape machines in studios at Bush and in some

BH studios only one or two machines which had to be operated by an

engineer: disks

could be taken

to the studio and played by Studio Managers (usually using the TD7

player with its groove locating mechanism - left), but tape inserts had

to be

played remotely from a central tape room. Tape had been in use for many

years for longer recordings, but with the introduction of smaller tape

machines into studios (and the increased reliability of tape which

meant that an engineer's attendance wasn't necessary) the disk system

was phased out.

Another

reason for the continued use of disks

was

that up until the

late 1960s there were no tape machines in studios at Bush and in some

BH studios only one or two machines which had to be operated by an

engineer: disks

could be taken

to the studio and played by Studio Managers (usually using the TD7

player with its groove locating mechanism - left), but tape inserts had

to be

played remotely from a central tape room. Tape had been in use for many

years for longer recordings, but with the introduction of smaller tape

machines into studios (and the increased reliability of tape which

meant that an engineer's attendance wasn't necessary) the disk system

was phased out.

The development of modern magnetic recording tape is covered on the next page.

1 INTRODUCTION

2 STEEL TAPE

3 OPTICAL FILM

4 DIRECTLY-CUT DISKS

5 MAGNETIC TAPE

6 PORTABLE RECORDING

7 CARTS AND DARTS

8 DIGITAL RECORDING AND PLAYOUT

The normal method of producing gramophone records was not suitable for the BBC because of the long delay before a playable copy could be made (and the cost). From the early 1930s a British inventor, Cecil Watts, was working on a form of disk which could be played back immediately: by 1934 he had a workable method involving a laquer coating on an aluminium disk and was running a firm called M.S.S. to manufacture them and the disk-cutters. The blanks could be cut in the same way as wax blanks had been, but could be played back immediately - though obviously the laquer was much softer than a normal gramophone record and repeated playings would wear it much more quickly. The BBC started experimenting with this: at first there were difficulties because of the quality of the lacquer but eventually things settled down and the system came into regular use. The photo shows a M.S.S. disk-cutting channel, the first type the BBC used.

The

process was more suited to short items than

full-length programmes - though it was perfectly possible, with two

machines, to change over, recording a 30 second overlap.

On playback the engineer would start the second disk, listening on headphones, pull it into sync by spinning or holding back the turntable (which wasn't heavy) and changing over once the two matched: though requiring some skill it isn't as impossible a task as it sounds (I've done it myself).

Disk recording was particularly suited to making location recordings, and the model C disk-cutter (right) was developed; this could be carried in an ordinary car and used to record interviews and so on. (This would be termed a 'transportable' machine, i.e. not actually bolted down: truly 'portable' machines would mean capable of being carried by one person).

With the onset

of the war came

a requirement for reporters in battle

zones to be able to record reports. and so the BBC midget recorder was

developed. This was truly portable, though still very heavy, and used a

clockwork spring - as used in ordinary wind-up gramophones - to drive

the turntable, thus removing a lot of strain from the battery (which

still of course had to power a valve amplifier). The photo shows

Frank Gillard using one in action.

With the onset

of the war came

a requirement for reporters in battle

zones to be able to record reports. and so the BBC midget recorder was

developed. This was truly portable, though still very heavy, and used a

clockwork spring - as used in ordinary wind-up gramophones - to drive

the turntable, thus removing a lot of strain from the battery (which

still of course had to power a valve amplifier). The photo shows

Frank Gillard using one in action.The onset of the war was also a driving force in the development of the disk recording. In 1941 a number of American Presto machines (below) were provided by the USA under lease-lend (some of these were intercepted and landed up at the bottom of the Atlantic). Many of these were for the Overseas Service at Bush House and were still in use over twenty years later: I cut a large number of disks on these as a young Engineer. The quality was surprisingly good - in fact better than 15 inches-per-second tape on the first play, though they did sound noisier once the producer had taken them to his office and played them a few times.

The

recording channels posed a safety risk: though for some reason normally

referred to as 'acetates' the laquer was in fact cellulose nitrate -

the same as non-safety cinema film. When you cut a disk the off-cut

comes off as a ribbon, called swarf. Although the cellulose nitrate is

safe enough when it's on the base, because this swarf is mixed with air

it is extremely inflammable. When I was on the training course at

Evesham the lecturer took a handful of the stuff outside onto the

concrete and dropped a match on it (I suspect this was to discourage us

from trying it). It went up immediately in six feet of flame, and I

could feel the heat on my face ten feet away - it's that dangerous.

The

recording channels posed a safety risk: though for some reason normally

referred to as 'acetates' the laquer was in fact cellulose nitrate -

the same as non-safety cinema film. When you cut a disk the off-cut

comes off as a ribbon, called swarf. Although the cellulose nitrate is

safe enough when it's on the base, because this swarf is mixed with air

it is extremely inflammable. When I was on the training course at

Evesham the lecturer took a handful of the stuff outside onto the

concrete and dropped a match on it (I suspect this was to discourage us

from trying it). It went up immediately in six feet of flame, and I

could feel the heat on my face ten feet away - it's that dangerous.There is a legend that, at the BBC Studios in Oxford Street (which closed in 1957) a producer (later a well-known politician) knocked his pipe out in a bin marked 'fire' (thinking it contained sand) and the swarf in it set fire to the recording channel. At Bush House another producer dropped a match (which had gone out but was still warm) in a bin - this time the engineer had the presence of mind to put his foot on the bin, so there was no fire, but the fumes got into the ventilation system and caused the evacuation of the entire floor.

One of the cleaners saw some of this soft black stuff and took it home and stuffed a cushion with it... very fortunately someone found out about it and she was discouraged. She might as well have taken an incendiary bomb home - if someone had ignited it, it would have burned her house down.

The

Prestos served us well, and were still working reliably when they were

phased out in the mid-1960s; we also had several BBC Type D

disk-cutting channels, and though these were no better in the already

very good quality

of the finished result, they were much easier to handle, with a better

vacuum-clearance of swarf than the Prestos, push-button scrolling

rather than a handle to turn, and much easier line-up. (In both cases

not only did test cuts with a fixed-frequency tone have to be made to

get the level right, but the grooves had to be examined with a

microscope as you cut the test so that you could adjust the depth of

cut).

The

Prestos served us well, and were still working reliably when they were

phased out in the mid-1960s; we also had several BBC Type D

disk-cutting channels, and though these were no better in the already

very good quality

of the finished result, they were much easier to handle, with a better

vacuum-clearance of swarf than the Prestos, push-button scrolling

rather than a handle to turn, and much easier line-up. (In both cases

not only did test cuts with a fixed-frequency tone have to be made to

get the level right, but the grooves had to be examined with a

microscope as you cut the test so that you could adjust the depth of

cut).Almost all these recordings were made at 78rpm. There had been some use of 60rpm in the early days but this had been abandoned. Indeed the 1950 BBC Recording Training Manual devotes two pages to a mathematical proof that recording at 54rpm increases the maximum time without degrading the quality, before concluding that as commercial recordings are made at 78rpm it's better to stick at that. Recordings were also made at 331/3rpm on 17 inch disks (using the same sized grooves as 78rpm): as one side would hold ten minutes this system was widely used at Broadcasting House for recording complete programmes.

Another

reason for the continued use of disks

was

that up until the

late 1960s there were no tape machines in studios at Bush and in some

BH studios only one or two machines which had to be operated by an

engineer: disks

could be taken

to the studio and played by Studio Managers (usually using the TD7

player with its groove locating mechanism - left), but tape inserts had

to be

played remotely from a central tape room. Tape had been in use for many

years for longer recordings, but with the introduction of smaller tape

machines into studios (and the increased reliability of tape which

meant that an engineer's attendance wasn't necessary) the disk system

was phased out.

Another

reason for the continued use of disks

was

that up until the

late 1960s there were no tape machines in studios at Bush and in some

BH studios only one or two machines which had to be operated by an

engineer: disks

could be taken

to the studio and played by Studio Managers (usually using the TD7

player with its groove locating mechanism - left), but tape inserts had

to be

played remotely from a central tape room. Tape had been in use for many

years for longer recordings, but with the introduction of smaller tape

machines into studios (and the increased reliability of tape which

meant that an engineer's attendance wasn't necessary) the disk system

was phased out.The development of modern magnetic recording tape is covered on the next page.